or I Dropped My Microphone on Ravi Shankar’s Sitar.

The word “icon” is tossed around pretty freely these days, and I probably fling it out there more than most. But put the name Ravi Shankar next to “icon” and you reset that bar to stratospheric heights. There are only a few musicians who stand out as icons when you think of a particular music or instrument. For Be-Bop it’s Charlie Parker; for the electric guitar, Jimi Hendrix; for classical music, Beethoven. Add to that list Ravi Shankar, the first name you think of when Indian music and the sitar come up. And now, like those musicians, Ravi Shankar is gone.

The word “icon” is tossed around pretty freely these days, and I probably fling it out there more than most. But put the name Ravi Shankar next to “icon” and you reset that bar to stratospheric heights. There are only a few musicians who stand out as icons when you think of a particular music or instrument. For Be-Bop it’s Charlie Parker; for the electric guitar, Jimi Hendrix; for classical music, Beethoven. Add to that list Ravi Shankar, the first name you think of when Indian music and the sitar come up. And now, like those musicians, Ravi Shankar is gone.

When Ravi Shankar plays an alap, the slow, improvised introduction to a raga, he closes his eyes as if lost to the world.“Somehow I don’t know my eyes become closed especially those parts which are slow and serene,” said Shankar during one of my two interviews with the artist. “That’s when I cannot keep my eyes open and watch my listener or watch everything like one can do later on when one plays faster pieces. And that’s one place where I completely lose contact with the outside world.”

Ravi Shankar didn’t start out playing sitar. Born on April 7, 1920 in Varanasi, India, he began as a dancer in an international performance troupe led by his brother, Uday. Shankar traveled the world in his teenage years living a cosmopolitan life. Opening up the booklet of his 75th anniversary CD, In Celebration, I pointed out a photo of a young handsome man, his long black hair is slick backed and strings of beads crisscross his bare chest as he strikes a seductive pose that wouldn’t be out of place in a Prince video.

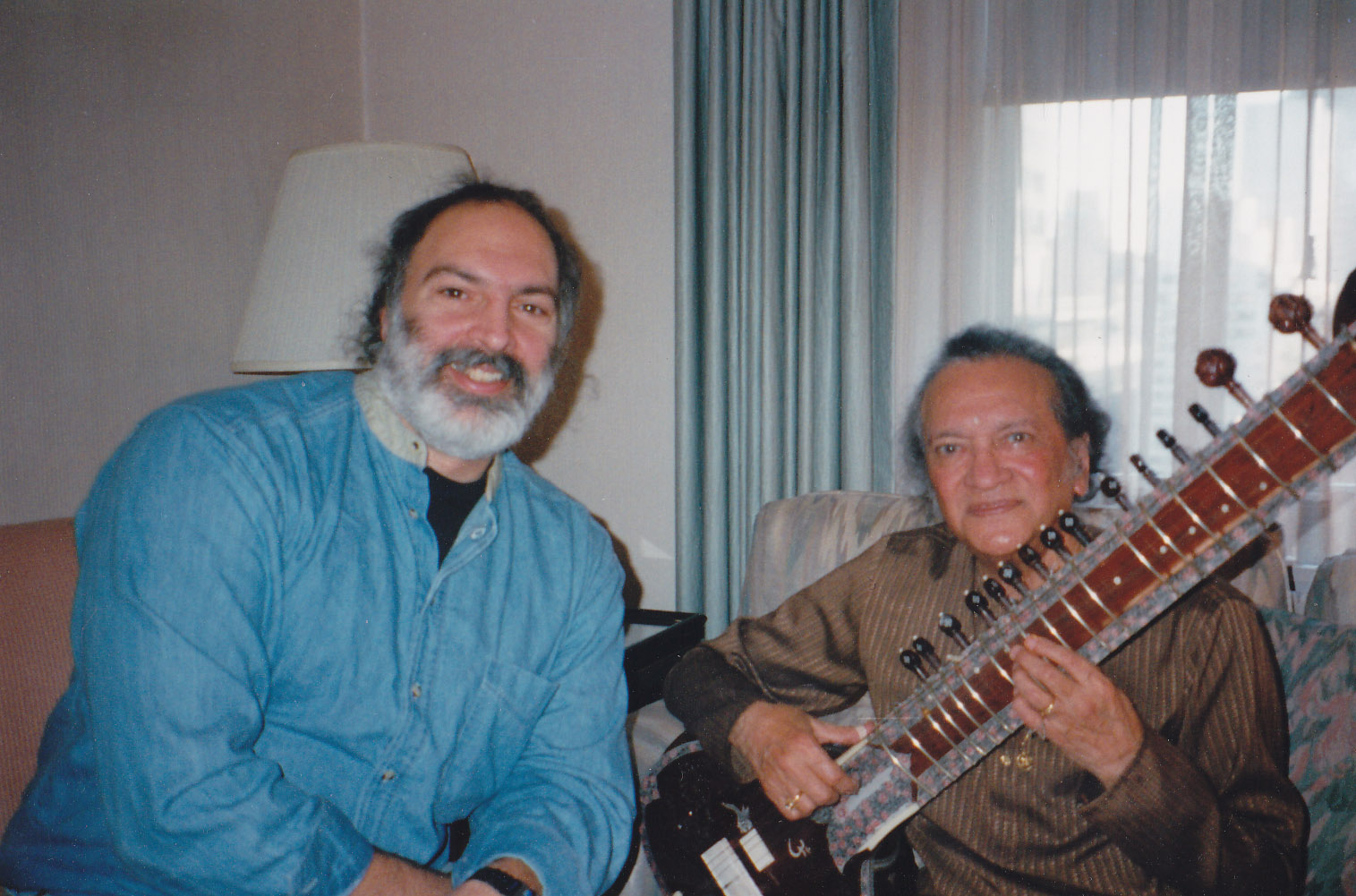

John Diliberto & Ravi Shankar, New York 1996

“Who is that young man?” I asked facetiously

“That’s me dancing,” laughed Shankar, looking at a picture of his teenage self. “This is my solo I choreographed myself.”

“How is this person different from the person sitting in front of me right now?” I probed.

“Well this person about 16 to 17 going 17, 19,” he answered. “And now I am going 76 almost. So there has to be a lot of difference, but I still have him inside me. I cannot get rid of him.

“What parts of him do you like?” I asked.

“Well that sometime I really feel like very young and very childish, especially after the sensation of coming to New York,” he said wistfully. “All my memories become so alive. My first sensation is the San Moritz Hotel in front of Central Park. That’s where we stayed. And New York was my first love, it’s very special. The whole Times Square, seeing 3 films a day, going to the Cotton Club, hearing Cab Calloway and all the famous people, seeing them on stage, Ed Wynn, Will Rogers, Eddie Cantor.”

That’s not the frame of reference that comes to mind when you think of Ravi Shankar. Even 16 years ago, Shankar was a frail man with a cloudy yellow ring around the irises of his eyes. But as he embraced his sitar, you couldn’t forget his stature as a master musician who seduced the world with an ancient sound and spirit. But before he attained a status of musical sainthood, he had to leave the world behind. In the midst of traveling the globe with his brother’s troupe, he decided to return to India with Master Baba Allaudin Khan and studied the sitar.

“I covered my eyes to all my near past and went to a very distant past,” reflected Shankar. “So it was a difficult job to do but I so wanted to acquire and learn music from this great man that I tried to live exactly the way he wanted: Old fashioned the old guru-disciple system. You become a celibate, you give up everything, you live a very simple life and nothing else but just work, you know.”

“I covered my eyes to all my near past and went to a very distant past,” reflected Shankar. “So it was a difficult job to do but I so wanted to acquire and learn music from this great man that I tried to live exactly the way he wanted: Old fashioned the old guru-disciple system. You become a celibate, you give up everything, you live a very simple life and nothing else but just work, you know.”

In fact, Shankar experienced the chilla, a forty day period of isolation and virtually non-stop playing. “That sort of thing is not possible today,” he conceded. He emerged from this stark period with formidable technique and a music whose spirit would suffuse several generations.

Almost from the beginning, Ravi Shankar reached out to other musicians, finding a common ground between Indian music and the jazz, rock and classical worlds.

“Imagine my background of those 8 years in Europe and America, listening to so much of world music at that time” he asked. “So it was very natural for me when I matured as a performing artist, that apart from keeping all the pure things there was something in my head going on to do new things, new expressions.”

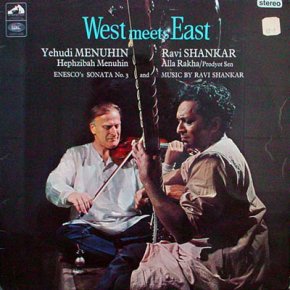

One of the first western musicians to embrace Shankar was classical violinist Yehudi Menuhin. They began paying together in the 1950s and in the late 60s recorded West Meets East.

And then came the 60s revolution when Indian music was embraced by psychedelic rock. It was this movement and Shankar’s association with George Harrison of The Beatles that really launched the sitarist towards global renown. But he has always been disparaging of the times even though he made notorious appearances at the Woodstock and Monterey Festivals as well as The Concert For Bangladesh, where the audience mistook his tuning for an actual piece music.

“And many times I had to walk off with my sitar really because I couldn’t take it anymore,” he ruefully recalled, “because our music is so sacred to us. But they took it for granted because George happened to be my student. So they took it for granted they come with the same spirit to hear our music, whistling and shrieking and doing all sort of things.”

Jazz saxophonist John Coltrane dialed into Indian modalities in the mid-60s through Shankar..

“I taught him the rudiments of our ragas and the way we improvise,” remembered Shankar. “He was so interested to know how we can create such peace, the feeling of tranquility in music. I used to tell him, ‘John, I’m amazed.’ Because when I saw him he had become a vegetarian, he had left drugs, drink, everything. He was studying Rama Krishna. So I asked him ‘Why do I find so much disturbance in your discordant in your music?’ So he said, ‘That’s what I want to find out, if you can help me, Ravi.’

Philip Glass tuned up his minimalist concepts while arranging Ravi Shankar compositions for orchestra. Space music bands like Popol Vuh dialed in to Shankar’s raga excursions and countless guitarists like Terje Rypdal and John McLaughlin brought Indian phrasing into their playing. World fusion was born in Shankar-influenced groups like Oregon, Shakti, and Ancient Future, all of whom ingested Indian music through Shankar.

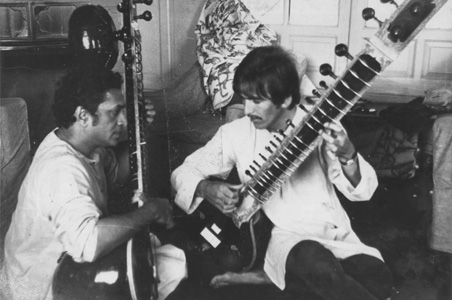

Ravi Shankar & George Harrison

Despite his misgivings, the 1960s and early 70s were times of feverish collaborations by Shankar, especially working with George Harrison. It’s something he picked up on again in the late 1980s when he made three albums for the Private Music label, including collaboration with Philip Glass, the minimalist who has cited Shankar as a primary influence. But no matter what the combination, Shankar says he’s still bringing the same spirit to the music which he learned from his guru, Baba Alaudin Khan.

“We always had oral tradition,” reflected Shankar. So the guru taught the disciple and along with the music it was not just the technique of some of the compositions but it was the whole spirit the whole way of life the whole religious aspect. The deep introspective feeling brought tears to the eyes, made you feel like you were near the god. That still exists in our music. And that’s something which I have been trying in many of my compositions. If you hear pieces like “Shanti Mantra,” you’ll see I have utilized western musicians, western choir and also things I tried to bring that feeling.”

He taught that oral tradition to his daughter, sitarist Anoushka Shankar. I first met Anoushka at her father’s home in Southern California. She was 19 then and just on the precipice of her own musical career. Sitting in their practice room, Ravi Shankar sang melodies and Anoushka played them back. As he played improvised lines on his sitar, fresh in the moment, Anoushka shook her head from side to side, acknowledging the mastery of his melodies even as she replicated them herself.

Ravi & Anoushka Shankar

“It’s very much a call and response type of situation,” she explained. “When he is teaching me, he’s either playing a composition that he is teaching me or he’s improvising. I watch him and listen and repeat, and it’s that sort of repetitive process of just playing it over and over again. It sinks in after a while.”

“We always had oral tradition,” her father concurred. “But it was also the whole spirit, the whole way of life, the religious aspect, to make you feel being near the god. That still exists in our music.”

For all his spiritualism, Shankar was a man of the world. He laughed easily and I can still remember him opening his fortune cookie in a Chinese restaurant. “You will have a happy life,” read the fortune, to which Shankar added, laughing hysterically, “in bed.”

And he was gracious. In our first interview in 1996, Shankar had demonstrated his sitar for me and was still holding it in his lap as we talked. For some reason, my microphone slipped out of my hand and crashed into his sitar. I stood frozen, as did his entourage around me. Before I could utter an apology, Shankar reached out and said, “It’s okay. It’s only a practice sitar.”

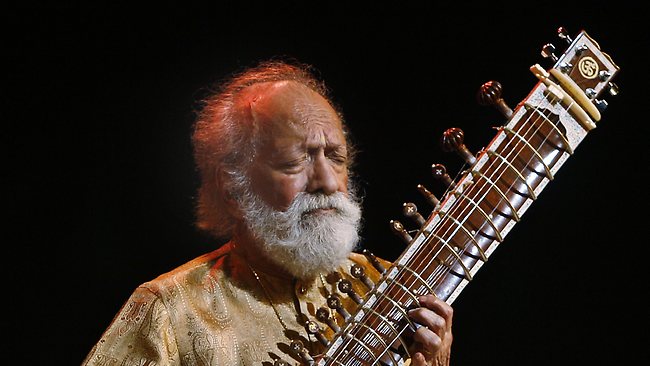

Ravi Shankar Towards the End

It didn’t matter what kind of sitar Shankar played, the logic and invention of his solos was extraordinary and his quicksilver interplay with tabla players like Alla Rahka is the stuff that would inspire jazz and rock musicians for decades. The concerts that I saw him play were always transporting experiences as Shankar wove entire worlds with his ragas.

Shankar was the last of an Indian music triumvirate that including sarod master Ali Akbar Khan and tabla master Alla Rahka. Ravi Shankar passed away last night, December 11, 2012 at the age of 92. It truly is the end of an era, but his influence resonates like the sympathetic strings of the sitar.

You’ll find of a list of Five Essential Ravi Shankar CDs that I compiled for his 90th birthday.

~© 2012 John Diliberto ((( echoes )))

Thanks for the article John. Well done.

~darin schaffer