Vangelis Remembered: A Synthesizer God Ascends

by John Diliberto 05/20/2022

Hear Echoes tribute to Vangelis on Monday, May 23rd.

A true God of electronic music, Vangelis has ascended to the heavens on May 17, 2022 at age 79. Although his glory days were in the 1970s and 80s, he was just coming back into form with recent albums like Rosetta and Juno to Jupiter.

I still remember my first Vangelis album, his second or third, depending on how you count them. It was Heaven and Hell. Steve Pross, a DJ at WXPN in Philadelphia where I was Music Director, had brought it over from England before its US release in 1975. It was a revelation. Heaven and Hell is a symphonic synthesizer masterpiece, a clarion charge from the skies. And most of it is done with just two early synthesizers and a roomful of percussion. Vangelis created a world of possibilities and grandeur that had not been heard since the dawn of the 20th century. I followed Vangelis avidly through his next releases. My first CD was Vangelis’s Mask, bought in London in 1985. I didn’t even have a CD player yet. It felt like a personal triumph when he scored Chariots of Fire and won the Academy Award for it. It was only the second electronic film score to win the Oscar.

I still remember my first Vangelis album, his second or third, depending on how you count them. It was Heaven and Hell. Steve Pross, a DJ at WXPN in Philadelphia where I was Music Director, had brought it over from England before its US release in 1975. It was a revelation. Heaven and Hell is a symphonic synthesizer masterpiece, a clarion charge from the skies. And most of it is done with just two early synthesizers and a roomful of percussion. Vangelis created a world of possibilities and grandeur that had not been heard since the dawn of the 20th century. I followed Vangelis avidly through his next releases. My first CD was Vangelis’s Mask, bought in London in 1985. I didn’t even have a CD player yet. It felt like a personal triumph when he scored Chariots of Fire and won the Academy Award for it. It was only the second electronic film score to win the Oscar.

Vangelis is an artist better-known by his work than his name. These days, mention the Greek synthesist to the general public and you’ll likely get a quizzical stare. Remind them that he scored Chariots of Fire, his Academy Award winning score from 1981, or Blade Runner from 1994 and their eyes light up in recognition.

It wasn’t that way in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Vangelis was turning up in film scores (The Year of Living Dangerously, Missing, Blade Runner,) being adapted for commercials (Mercury Lynx.) and topping international charts in collaborations with Yes singer Jon Anderson. But since the peak of the New Age movement in 1985, Vangelis’s synthesized blend of the dramatic and the bombastic, the heart-rending and the sentimental, has fallen from favor. His name has faded from consciousness in America, right along with Peter Max, Tom Robbins and other one-time avatars of a new consciousness. Another Greek synthesist with a singular stage name, Yanni, took his place in the public’s minds and on the charts for a while, but his fame has faded as well: make a Yanni joke today and no one under 50 will get it.

Yet, while fewer people were listening, Vangelis continued to extend his sound over the years since Chariots of Fire, making some of his best music ,including the gothic chorales of Mask, collaborations with singers like Stina Nordenstam and Caroline Lavelle on Voices, the perfectly tuned ambient designs of Soil Festivities and the grand orchestral synthesizer expanse of his score to Ridley Scott’s 1492: The Conquest of Paradise.

Yet, while fewer people were listening, Vangelis continued to extend his sound over the years since Chariots of Fire, making some of his best music ,including the gothic chorales of Mask, collaborations with singers like Stina Nordenstam and Caroline Lavelle on Voices, the perfectly tuned ambient designs of Soil Festivities and the grand orchestral synthesizer expanse of his score to Ridley Scott’s 1492: The Conquest of Paradise.

Vangelis was an anachronism in that he was an electronic musician who didn’t used computers. When he played, it was all live on the floor. I interviewed him in 1982 at his Nemo Studio in London. It was just a few days after he’d won the Oscar for Chariots of Fire and while he was putting the finishing touches on Blade Runner. He sat down at his then all-analog keyboards and whipped out a piece right in front of me that was layered and sequenced all in real time. I caught in on my little ElectroVoice 635A omni microphone and a Nakamichi cassette deck. Years later, I saw him do the same thing in Athens for the live performance and taping of his orchestral work, Mythodea. On stage were 24 timpani drummers, a 100-voice choir, a 70-piece orchestra and two opera singers. In the middle, buried behind an imposing black ebony cockpit suitable for Darth Vader, was Vangelis, pouring out synthesizer designs in real time. I went behind his set-up and saw an array of foot pedals, keyboards and other controllers, all deployed in the moment, not on tape. In the days when Vangelis gave solo performances, his concert program had an admonition that “Vangelis does not employ the use of pre-recorded tapes or programs during his performance.”

That was the beauty of Vangelis. He let his inspiration fly. Even though he played in a rock band and had the psychedelic/progressive rock group Aphrodite’s Child from 1968-1972, this was not his world. However, if you want to have the shit scared out of you, listen to “Infinity” from the double Aphrodite’s Child album, 666. No one could bring on the apocalypse like Vangelis.

Vangelis sculpted space and time on albums like Albedo 0.39 and Spiral. He’s one of the few musicians whose loss was lamented by NASA.

He says he composed everything in one flight and I believe him. He was asked to join Yes when keyboardist Rick Wakeman left, but Yes singer Jon Anderson said he was too free-wheeling and spontaneous for the precisely-calculated progressive rock of Yes.

He says he composed everything in one flight and I believe him. He was asked to join Yes when keyboardist Rick Wakeman left, but Yes singer Jon Anderson said he was too free-wheeling and spontaneous for the precisely-calculated progressive rock of Yes.

Listening to key Vangelis records was like entering an imaginary landscape. These were recordings that were meant to be journeys. Albums like Oceanic, Voices and The City found Vangelis working with new textures and structures that went beyond sequencer clichés. Vangelis could sometimes be overly sweet. He could really milk those synthesizer note bends and vibrato to wring-out the tears of the susceptible. But he also created works of profound poignancy like “L’Enfant” from 1979’s Opera Sauvage. Built around a one-note sequencer pattern, Vangelis created a melody that sounded like a madrigal transfigured. That track was used in the film The Year of Living Dangerously and it totally eclipsed Maurice Jarre’s score for that movie.

Listening to key Vangelis records was like entering an imaginary landscape. These were recordings that were meant to be journeys. Albums like Oceanic, Voices and The City found Vangelis working with new textures and structures that went beyond sequencer clichés. Vangelis could sometimes be overly sweet. He could really milk those synthesizer note bends and vibrato to wring-out the tears of the susceptible. But he also created works of profound poignancy like “L’Enfant” from 1979’s Opera Sauvage. Built around a one-note sequencer pattern, Vangelis created a melody that sounded like a madrigal transfigured. That track was used in the film The Year of Living Dangerously and it totally eclipsed Maurice Jarre’s score for that movie.

But as sweet as his music could be, he also wrote the book for dystopian electronic music with his 1982 score to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. It is still a signpost for most electronic artists.

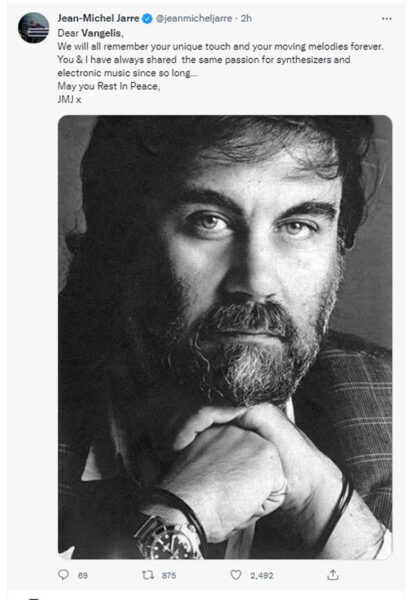

Born Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíou, Vangelis was bigger than life. A large man with full black beard and long black hair, he was gregarious, affable and, well, arrogant, but in a mostly endearing way. When I interviewed him a second time in Athens during his performance of Mythodea, he’d gotten a little more portly in that late-Orson Welles kind of way, punctuating his comments with a wave of a thick cigar.

There are a lot of artists who can get large orchestras and impressive venues in which to play their music. But how many could compose an opus to Mars and have the planet itself rise above the stage in mid-performance, sitting, no less, at its brightest point and closest proximity to earth? Somehow, Vangelis accomplished that for his performance of Mythodea in 2001 at the Temple of Zeus. “I just called Jupiter before the concert and I said can you arrange for Mars to be in the middle of the stage and quite bright, please,” he said a few days later. He did wink, although the fact he thought that was necessary says something about how Vangelis thought he might be perceived.

There are a lot of artists who can get large orchestras and impressive venues in which to play their music. But how many could compose an opus to Mars and have the planet itself rise above the stage in mid-performance, sitting, no less, at its brightest point and closest proximity to earth? Somehow, Vangelis accomplished that for his performance of Mythodea in 2001 at the Temple of Zeus. “I just called Jupiter before the concert and I said can you arrange for Mars to be in the middle of the stage and quite bright, please,” he said a few days later. He did wink, although the fact he thought that was necessary says something about how Vangelis thought he might be perceived.

Vangelis left us with a wealth of ear-stretching music that carved beauty out of circuits. And even in his later years, after a long fallow period, he dropped the albums Rosetta in 2016 and Juno to Jupiter only last year. The next time you’re running down a beach, walking through a blasted city landscape or rocketing into space, remember that Vangelis created the perfect score for your journey. Vangelis told me that music is “there, it’s before me and it’s after me. I’m somewhere in the middle and I’m like a wire and like a bridge between something.” Vangelis, his music is now traveling the wires and threads of time.

A beautiful tribute to an amazing man. His collaborations with Demis Roussos make me weep to this day.

Great musical genius. Rest easy.

Thank you, John, for the tribute. I love Vangelis. And I personally would like to thank you for one very late humid night in March, 2000, when you played on the radio “Incantations”, by Mike Oldfield. It was magical on so many levels, that will require too many pages to describe. Thank you!

Thank you so much!