Chick Corea, Fusion Pioneer, Leaves the Planet

by John Diliberto 2/12/2021

Chick Corea made a music of joy. Whether composing, improvising, or leading one of his many groundbreaking ensembles, he entered music to explore and communicate. From compositions like “Spain” and “Captain Marvel” to groups like Circle and Return To Forever, Chick Corea used a touch, “light as a feather,” to leave an indelible mark on jazz. I know for my generation, his work with Return to Forever, especially the electric edition with Al Di Meola, Stanley Clarke and Lenny White, supercharged the mid-1970s. The music was called fusion or jazz fusion and the jazz purists hated it. But, what they didn’t get was, it wasn’t jazz. It was a new form of music even more different jazz than be-bop was from swing. It had the energy and instrumentation of rock, particularly heavy metal and progressive rock, but it had the exploratory nature and virtuosity of jazz. Artists like Chick Corea, The Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report and Herbie Hancock merged these into a new synthesis.

Chick Corea made a music of joy. Whether composing, improvising, or leading one of his many groundbreaking ensembles, he entered music to explore and communicate. From compositions like “Spain” and “Captain Marvel” to groups like Circle and Return To Forever, Chick Corea used a touch, “light as a feather,” to leave an indelible mark on jazz. I know for my generation, his work with Return to Forever, especially the electric edition with Al Di Meola, Stanley Clarke and Lenny White, supercharged the mid-1970s. The music was called fusion or jazz fusion and the jazz purists hated it. But, what they didn’t get was, it wasn’t jazz. It was a new form of music even more different jazz than be-bop was from swing. It had the energy and instrumentation of rock, particularly heavy metal and progressive rock, but it had the exploratory nature and virtuosity of jazz. Artists like Chick Corea, The Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report and Herbie Hancock merged these into a new synthesis.

But Corea always had a different sensibility. When he sat down at the piano, there was a sense of ease that came from his performance. Notes flowed with an inner logic and design, even in his most spontaneous improvisations. For the last 60 years, Corea used his virtuoso technique to navigate a course through contemporary jazz, riding with the currents of fusion, stirring up the eddies of the avant-garde, and dipping into the wellspring of classical music.

Chick Corea was surrounded by music from the day he was born into an Italian household, on June 12th, 1941, in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He was named Armando Anthony Corea, after his father, Armando John Corea, a trumpet player on the Boston jazz scene. Musicians were always around their house after gigs and his mother would make pasta. His father would bring home the latest jazz 78s, including the first recordings of Miles Davis with Charlie Parker. It wasn’t long before Chick Corea was playing music himself. A child prodigy, he got a piano when he was four and took lessons from classical pianist Salvatore Sullo. But the jazz die was already cast. He auditioned for his lessons by playing Dizzy Gillespie’s “Perdido.” At five years old he wanted to play like Bud Powell. He couldn’t do that as a five or six-year-old, but he did as a 56-year-old in 1997, when he recorded Remembering Bud Powell.

Chick Corea was surrounded by music from the day he was born into an Italian household, on June 12th, 1941, in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He was named Armando Anthony Corea, after his father, Armando John Corea, a trumpet player on the Boston jazz scene. Musicians were always around their house after gigs and his mother would make pasta. His father would bring home the latest jazz 78s, including the first recordings of Miles Davis with Charlie Parker. It wasn’t long before Chick Corea was playing music himself. A child prodigy, he got a piano when he was four and took lessons from classical pianist Salvatore Sullo. But the jazz die was already cast. He auditioned for his lessons by playing Dizzy Gillespie’s “Perdido.” At five years old he wanted to play like Bud Powell. He couldn’t do that as a five or six-year-old, but he did as a 56-year-old in 1997, when he recorded Remembering Bud Powell.

As a teenager in the 1950s, Corea led his own groups, playing everything from dances to weddings. But the pianist already knew he had to get to New York City to pursue his jazz dreams. He enrolled at Columbia University, but took classes with “Professor Jazz,” attending classes at Birdland as much as Columbia. There he saw The Miles Davis Quintet with John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones. Even when he transferred to the Juilliard School of Music he was often at the Village Vanguard and The Five Spot, eventually playing those clubs himself in bands led by Maynard Ferguson, Art Blakey, and Kenny Dorham. In 1962, Corea made his first recording with Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria on the album, Go, Mongo! It began his love of Latin music.

Corea went on to record with Sonny Stitt, Blue Mitchell, Stan Getz, and Hubert Laws. His stint with flutist Herbie Mann on the album Monday Night at yhe Village Gate in 1966 led to Mann signing Corea the Vortex label that he produced. Mann wanted him to make a Latin-inflected record, but Corea had other ideas. He was listening to John Coltrane, Miles Davis’s classic quintet, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. They were all in the vanguard of the avant-garde.

Chick Corea’s debut as a leader was Tones for Joan’s Bones, named for his first wife. His group included saxophonist Joe Farrell, trumpeter Woody Shaw, bassist Steve Swallow, and drummer Joe Chambers. In case you don’t know them, they were all monster players who were bandleaders in their own right. Corea established himself as an innovative band leader, recording the albums Sundance and The Song of Singing, that bridged the post-bop and free jazz worlds. His 1968 album, Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, is a landmark recording. Corea developed an incredible sense of intuitive interplay, carving out space in unison with musicians like bassist Miroslav Vitous and drummer Roy Haynes.

While working with singer Sarah Vaughan, he got “the call.” It came from a longtime Boston friend, drummer Tony Williams, asking Corea to substitute for Herbie Hancock on a gig with The Miles Davis Quintet. He would play with Miles Davis for two years on some of the trumpeter’s most influential albums, including In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew. And, as with many of Miles’s pianists in the late 1960s, Corea was urged to play electric keyboards.

While working with singer Sarah Vaughan, he got “the call.” It came from a longtime Boston friend, drummer Tony Williams, asking Corea to substitute for Herbie Hancock on a gig with The Miles Davis Quintet. He would play with Miles Davis for two years on some of the trumpeter’s most influential albums, including In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew. And, as with many of Miles’s pianists in the late 1960s, Corea was urged to play electric keyboards.

Chick Corea had the opportunity play free with Miles, especially when the trumpeter left the stage. Corea left the group with bassist Dave Holland to continue their free-form improvisations as Circle with drummer Barry Altschul and saxophonist Anthony Braxton. They pursued a style of free playing that still retained structure, harmony and melody. They could be as delicate as a spring shower on a placid pond, and as stormy as a hurricane.

In 1968, Corea became a convert to Scientology, the controversial religion founded by L. Ron Hubbard, which altered Corea’s way of thinking and organizing. Guitarist Al Di Meola said Scientology gave Corea the certainty to never doubt a decision. It also provided the pathway to a more accessible sound that reached a much wider audience. That was the birth of Return to Forever. Initially, it was an introspective, expansively melodic quintet with bassist Stanley Clarke, saxophonist Joe Farrell, percussionist Airto Moreira and Airto’s wife, Brazilian singer Flora Purim.

This lineup spawned some of Corea’s best-known compositions, including “Senor Mouse,” “La Fiesta,” “Captain Marvel” and his most-covered song, “Spain.” This group marked Corea’s return to Latin and Spanish music. When he played it for me on piano in his home, he drew the line between Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain album, and Rodrigo’s “Concerto De Aranjuez.” “Spain” has been recorded over 100 times, by artists as diverse as The Munich Philharmonic, banjo player Bela Fleck, singer Al Jarreau, and even the Blue Devils Marching Band.

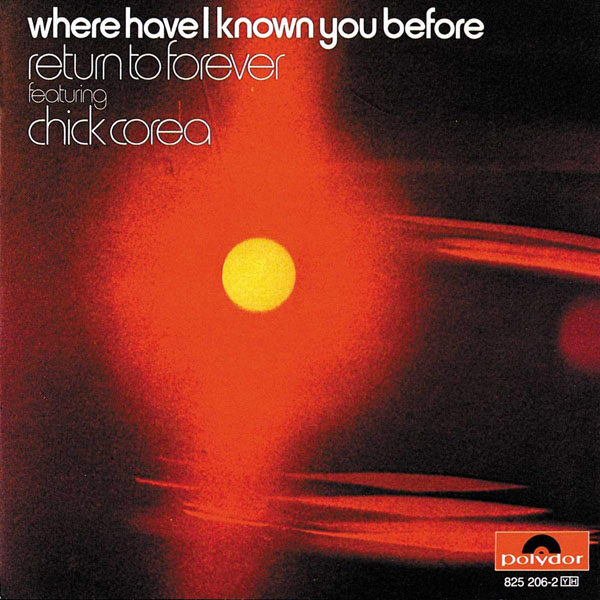

Return to Forever had attained critical and popular acclaim, but Chick Corea was already hearing a different sound and fury, one forged by The Mahavishnu Orchestra, led by guitarist John McLaughlin. Chick Corea went for the same brand of blistering electric fusion. He shifted Return to Forever’s lineup, dropping all but Stanley Clarke and adding guitarist Bill Connors and drummer Lenny White. This band forged Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. Al Di Meola replaced Connors, and that became the classic lineup of Return to Forever. With Return To Forever, Corea set his synthesizers on stun and they went from playing clubs to arenas. It wasn’t jazz, but it was powerful and popular. Many of the titles were drawn from the writings of Scientology and L. Ron Hubbard including Hymn to the Seventh Galaxy, Where Have I Known You Before.

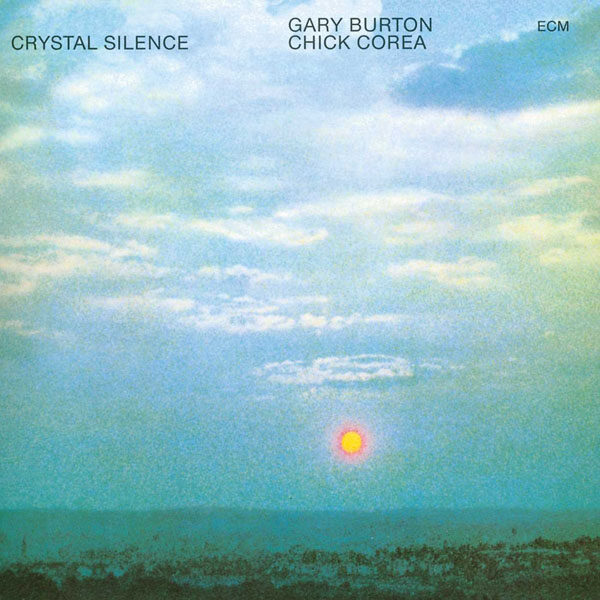

Like a pendulum, Corea never stayed at either end of the arc for long. Immediately before and after Return To Forever, Corea recorded solo piano improvisations on the German ECM label. He also engaged in a series of duets, including albums with pianist Herbie Hancock and vocalist Bobby McFerrin. But the most enduring was with vibraphonist Gary Burton. Together they recorded the 1972 album, Crystal Silence, followed by six more albums of duets.

Later in the 1970s, Chick Corea’s music became more whimsical and full of Spanish motifs, especially the album, My Spanish Heart. The cover depicted the pianist with his hair slicked back and his body clad in toreador regalia. Inspired by flamenco music, Corea’s piano playing took on Spanish flourishes.

Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Corea moved restlessly from project to project. He recorded in acoustic quartets, revisited his 60s trio sound with drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Miroslav Vitous, and even recorded classical compositions. His work was mostly acoustic, but in 1986, he plugged-in with a vengeance in a group he called The Chick Corea Elektric Band. Playing with younger musicians who grew up with his music, Corea used his keyboards to effect a more orchestral sound.

He ultimately went on to record a Mozart piano concerto, and then wrote his own. He recorded his “Concerto Number One for Piano and Orchestra” with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and had it released on the Sony Classical label.

As Chick Corea moved into the 21st century, his music showed no sign of abating. He recorded solo albums, trio albums, and with a big band called Origin. He ultimately re-formed Return to Forever for a successful tour and live album, but he was always looking for new dimensions.

Chick Corea left the planet on February 9th at the age of 79 after an apparently brief bout with cancer.

John Diliberto & Chick Corea 2001

Personally, I have fond memories of Corea. I got into his music with the electric Miles Davis groups, and soon discovered his early works like Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, which took me into avant-garde jazz dimensions. I followed him through Return to Forever and beyond. In the 1980s, I interviewed him for the Totally Wired radio series, and at the turn of the century I spoke with him again for NPR’s Jazz Profiles. I visited him in Clearwater, Florida, where he took me to dinner at the Scientology Center, and then to his home for an expansive interview, during which I got nauseous from food poisoning (from breakfast, not the Scientology meal). Chick and his wife, Gayle Moran, were so gracious nursing me back until I could continue talking with him. I spoke with him again during the Return to Forever reunion tour.

Although Chick was in an uncharacteristic and short-lived portly phase in this picture with me, he maintained the boyish face and trim looks that graced his album covers, as well as his enthusiasm for music, to the end. The enormous music room I saw when I interviewed him 20 years ago was testimony to his multiple interests. On one side was an electronic studio, next to that, a marimba. A full drum set sat next to a pair of concert grand pianos.

When I think of his greatest works, Circle, A.R.C., Crystal Silence, the duet albums with Herbie Hancock (phew), Return To Forever – from the debut, through to Romantic Warrior – I hear the sound of joy, the thrill of the moment and an unerring path to the future. He never became one of those older musicians treading the same path, and now his paths are in other, probably multiple dimensions.

John, thank you. A very thorough and touching tribute to one of my top 10 favorite modern jazzers. His death was a real punch in the gut I think because he has been so active and has been one of the leading lights in contemporary jazz right up to his dying day. My heart still sinks thinking about it.

Another of his contributions was discovering Hiromi for Western audiences. She has a wonderful recording with Chick simply entitled Duet. She came to town with Stanley Clarke for another fabulous duet performance and I had the privilege of speaking with both afterwards. She’s the Art Tatum of our age but you have to be selective with her. When she performs solo or with people of equal caliber she’s dynamite. But her trio albums – I’ll pass. As Tom Conrad complained, she too often approaches musicmaking as if it were a sport – her virtuosity gets in the way. The Sonicboom albums are OK, they’re just for fun.

Chick came to Salt Lake many times, but I was never able to attend – something always got in the way. A couple of years ago he was down at BYU with Marsalis and the LCJO for a Monk tribute, but I was in Vegas at a convention. Life isn’t fair

In conclusion, the first sentence of your tribute sums it up. My sentiments exactly.

Thank you. Chick was a great loss, but he gave us a lot of music to live with.