Jon Anderson’s 30-Year Old Lost Album Reborn

By John Diliberto

9/25/2020

Yes singer Jon Anderson talks about his new album, 1000 Hands, Yes, Kitaro, Ian Anderson and Vangelis.

There are few voices out there as distinctive as Jon Anderson‘s. The founder of progressive rock icons Yes, has a high pitched, choirboy yearning that cuts through even the most bombastic of Yes productions. He was the mystic shaman of Yes, taking them into deep philosophical terrain whether it was the epic Tales from Topographic Oceans or the hit single, Going for the One. Anderson has also released several solo recordings, the first being the multi-tracked masterpiece, Olias of Sunhillow, where Anderson played every instrument and layered his vocals in elaborate choirs.

There are few voices out there as distinctive as Jon Anderson‘s. The founder of progressive rock icons Yes, has a high pitched, choirboy yearning that cuts through even the most bombastic of Yes productions. He was the mystic shaman of Yes, taking them into deep philosophical terrain whether it was the epic Tales from Topographic Oceans or the hit single, Going for the One. Anderson has also released several solo recordings, the first being the multi-tracked masterpiece, Olias of Sunhillow, where Anderson played every instrument and layered his vocals in elaborate choirs.

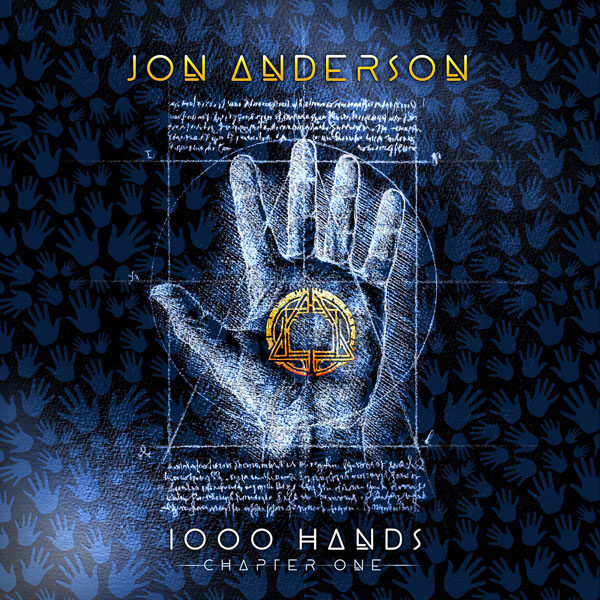

Last year, he released the album, 1000 Hands and it was recently re-issued on a new label. It’s an eclectic outing, mostly because of the heavy list of guest musicians, including Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson, for whom Yes opened on their first North American tour, Billy Cobham, Jean-Luc Ponty, Chick Corea, Zap Mama, Steve Morse, and Yes bandmates Chris Squire, Alan White, and Steve Howe. The album has a strange genesis. The original tapes were recorded 30 years ago. I spoke with Anderson on Zoom, at his home in the hills near Big Bear, California. It was supposed to be an Echoes on-air feature. The audio was not broadcast quality, but it was good enough to transcribe.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

JD: So you’ve been, you’re in California, right? And you’ve been in quarantine since March like most of us?

JA: Yeah, actually, the day we were told to go into quarantine, I was setting up the BBQ and I tripped on the step going down, and I broke two bones in my foot, so I was incapable of doing anything for two months. I had a boot on and my wife, god bless her, became a goddess because she learned to cook and take care of me, and look after everything. I couldn’t carry anything. So I was so blessed, but I could spend time int he studio, which was really cool, because I had a backlog of projects that need to be finished and that’s what happens when you need to stay home.

JD: So being under quarantine, does it make you feel like music is more of less meaningful.

JA: More, more. I think this amazing time, very much like the ‘60s, I would say that on tour last year that 2020 is gonna be like the ‘60s. I didn’t realize what I was prophesying, but I thought we need to change so much. We need to change our perception of mother earth and how we’re destroying our home, and how we’re destroying our collective consciousness, and we should wake up and dream. And that’s what the album is all about. I’ve been saying this for ages that change we must.

JD: Yes, you have. You have and I was thinking because I saw that quote from you, and I was thinking well, 2020 is kinda like the ‘60s. We’ve got protests, we’ve got police brutality, we’ve got war. We’ve got racial issues. The only thing on top of that is the pandemic.

JA: Which is not, not good at all. I was thinking about that just last night that the people that are dying are moving on to the next world, and we’ve got to start trying to realize that rather than death, and you get put in a coffin and the worms eat you up. There’s an old song from Lancashire about that. And that’s not the truth. Your state of consciousness is lasting and that’s the way I believe things are. And I haven’t been proved wrong at the moment, I just know that eventually we will go to the divine and that’s why we live, to find the divine within. And through music and poems, and songs, and art of every–of any kind, we reach out as humans to that collective consciousness.

JD: So you haven’t been proven wrong, but have you been proven right?

JA: For me, all religions are the same and in a same context. And we all have Christ’s consciousness around us all the time and within us, and this is a book I read in 1969 in London when I was just starting Yes. It was a book by a lady called Vera Stanley Alder, and it’s called The Finding of the Third Eye, which is the waking up of the dormant Pineal gland.

JD: Oh, okay.

JA: As things go.

JD: Well, you’ve kind of touched on those themes pretty much throughout your career.

JA: Sure, sure.

JD: So tell me, just give me the short story about One Thousand Hands. My understanding is that most of these songs go back 30 years?

JA: I was just coming out of touring with ABWH (Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman and Howe) and I needed a break and I went up to Big Bear, which is the mountain area just southeast of Los Angeles. And I got in touch with an old friend of mine, Brian Chatton, who used to be in my first band, The Warriors. He joined The Warriors in 1966, and he joined because he was 16.

JA: I was just coming out of touring with ABWH (Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman and Howe) and I needed a break and I went up to Big Bear, which is the mountain area just southeast of Los Angeles. And I got in touch with an old friend of mine, Brian Chatton, who used to be in my first band, The Warriors. He joined The Warriors in 1966, and he joined because he was 16.

So we kept up our friendship throughout the years and I asked him to write some music for me, I’m going up to Big Bear, I want to write some songs. And he sent me these beautiful pieces of music. And they became basically the, more or less, the crux of the album, 1000 Hands. But like in 1990, we just made the music, put ‘em on tape.

I went down to Los Angeles. I put Chris Squire and Alan White on a couple of tracks and started thinking. I think the best way to do this album is to get lots of people to join in. And I wanted to get Wayne Shorter from Weather Report, Billy Cobham from Mahavishnu Orchestra, people like that. I thought would be really cool, even the Beach Boys. I’d love to get them to sing.

So I called it Uslot: a lot of us. And then we put the tapes in the garage for 26 years. And then Michael Franklin, who knew Brain Chapman and knew about the project, called me up two years ago and said to me, “What’s happening with those tapes?” And I said, you know, “Which tapes? I don’t have any tapes.” He said, “You know, the 24 track tapes.” I said, “Oh yeah, they’re in the garage collecting dust.”

So I sent them to him. He put them in an oven to bake them, played them once, straight to the computer and they sounded amazing. The songs sounded really good. And of course, Michael Franklin, being a very good producer, understood what I was saying about adding certain musicians. He knew Billy Cobham. He got in touch with Ian Anderson, I got Jean-Luc Ponty to play on a track because I’d just finished working with him three years ago. And the rest is sort of Michael Franklin, the producer. We got so many people, it was amazing to play on the album.

JD: So did you record new tracks yourself, new vocal tracks?

JA: I did send him some vocalizing tracks which I do almost every day, which is the idea: I wake up and I start doing some vocalizing, rhythmic vocalizing, which is based on a video I saw many, many years ago about pygmies in West Africa, who go out foraging and hunting; they sing all the time, like “bee-n-bah,” and “bee-n-bah” and “bee-n-bah…” and another one would go “be-bo-ba,” and the insects and the birds sing along with them. It’s kind of very magical. So that’s what I’d do. And I picked out two of these vocalizing pieces, both are about four minutes long, sent them to Michael Franklin, and he loved them and took them on a plane ride to China, and on the way to China through his computer, his laptop, he did all the music. And I thought, isn’t that so cool that these days you can make music like that because he did an incredible job with the musical side of that, those tracks. Woo.

JD: So, so the title, 1000 Hands, comes from…?

JA: Well, I wrote on my Facebook 10 years ago about 150 people that have influenced my life. I wanted to let people know all the people that, you know, artists, musicians, singers, architects and so on, and writers, and I kept thinking how many people that I’ve known over the years, it’s kind of amazing that have helped me through my life. And Michael said well why don’t we call the album 1000 Hands. That’s a very significant phrase in Chinese, and I said yeah, I like that, 1000 Hands.

JD: It’s quite a different way of making a record than Olias of Sunhillow.

JA: The opposite. Olias, I did on my own and strangely enough, here I am 40 years later, 45 years later, I think, working on a follow-up, which I started 15 years ago because my son Damien said why don’t you do another Olias? Why don’t you do Son of Olias? And I said okay. And I’ve been working on it ever since and driving myself crazy, but now, because I have this time, I’ve set up my harp and my koto, and other instruments. And I’m actually working on Part 2. It’s crazy.

JD: Oh, well, excellent, because you know, I listened back to it for the first time in a while. Sound still sounds amazing.

JA: It’s a trip isn’t it?

JD: Yes.

JA: Totally by myself. I had an engineer and I learned – I actually went to music school in my garage, my learning all the instruments.

JD: So you were mentioning the pygmies and that kind of thing is on the tunes, “Ramalama” and “Where Does Music Come From,” right?

JA: Yeah.

JD: With “Ramalama” though, I was thinking: were you a doo-wop fan?

JA: I’d forgotten about that song, “Rama Lama Ding Dong” (1957 hit by The Edsels) until last week. And somebody told me, oh you remember “Rama Lama Ding Dong” Because I was told that ramalama was an Indian name for higher thinking. What do I know?

JD: Well, maybe it is higher thinking, you know. It’s coming to you in a different way.

JA: Yeah.

JD: So “First Born Leaders” is a really interesting track because it starts out with a gospel choir.

JA: Sure.

JD: What inspired that part of it?

JA: Well, this was recorded in the mountains there, and I had this thinking that we are from the ‘60s, the hippies, and we’re the first born leaders and we have to lead the younger people now, and especially the children and grandchildren. And the idea became a logical thing as a starter for a very simple song that I had about all these people. It’s just a song about what you want or what you need and everything is really right within you: you don’t have to look for it out there.

You tend to want things that are out there materialistically or even got to go to church to find god and things like that. And when everything, your church, is within. And I don’t say that in the song, but that’s basically what I’m getting at.

JD: No, I think you do say it in the song actually. But I’m wondering, what did the gospel choir mean for you in that song?

JA: I just love those choirs. The, the idea of spending time and listening to gospel choirs is an extraordinary feeling, and you know, it’s one of the things, I just said have you got a gospel choir, Michael? And he said yeah, I know one just around the corner in the church. And I said well get them to sing along with you guys and make it sound, like, very churchifying.

JD: So there must be a little bit of bittersweetness to this album. It actually came out last year, right, about a year and a couple months ago?

JA: Sure.

JD: And now it’s being rereleased.

JA: Yeah.

JD: But there’s a few people on this album, of course, who are no longer with us.

JA: That’s very true, Chris Squire. I said why don’t you play on this song, and here’s a couple of grand, and I’ve got money to make an album. And they were happy to play on it, and of course, Chris, magnificent bass player that he was, he just played. And I said, “How do you do that?” And he looked at me and said “Jon, I’ve been doing it for 40 years with you.”

JD: And Larry Coryell is on it as well.

JA: Larry Coryell, it’s one of those things, you know, you wanted to get people on. And then he, he went to the next level after. And amazingly, Zap Mama, who I met in 1991, I went to see Kitaro, and these girls from Belgium opened up for Kitaro. I didn’t actually meet them, I saw them. To get them on the album was magical because I didn’t ask Michael. He just found them and said oh, I’ve just put Zap Mama on as well. And I said Michael, you’re reading my mind here!

JD: So having Ian Anderson on there must have taken you back to your, what, first tour, first US tour with ?

JA: Yes, Ian Anderson was a guy that I first saw in the Speakeasy Club in London and he had a long mack on, a lot of beard. He looked like a tramp, but man, he could play the flute. And the band was great. And then we went on tour with them and that first show was spellbinding for me because it was the first time I played in front of 5,000 people. Kind of an amazing auditorium in Canada. And I was very shy. I was standing back, singing, playing the tambourine maybe, and just standing still, getting on with my concentrating on singing. And he comes on, he’s the showman. And he starts dancing around and had his feet on his knees, how he did it, balancing and, and jiving the audience like crazy.

So in the first week I realized he did the same shows every night, so he had it all choreographed mentally. And it taught me to be a little bit looser on stage, and move around on stage at certain points in a song, so I’d run over to Chris at a certain point where he’s doing bass part. And walk over to Steve and wave or something, anything to liven, liven up the show. So, I said to Ian at the end, thanks for being on tour together, because you’ve taught me a lot of things. And he’s the sweetest guy.

JD: So, “Activate,” which is one of the songs that he’s on, is far and away the most sweeping piece on the album. And I’ve got a few questions about it.

JA: Sure.

JD: Okay, so first, what are Proposition 4673 and 3542?

JA: Well, very simply, when I was driving around up to Big Bear, I kept seeing these signs in people’s garden for Proposition 33, Vote Yes, and then another, Proposition 72, Vote No. It was that time of the year where people have to vote for whatever. And it just rang in my head. And I thought oh yeah, “Proposition 3542 means that everything begins and ends with you,” of course. I write that down. You know, I do most of my lyrics very spontaneously and they became sort of an idea: vote for yourself, you know, vote for me, vote for yourself to be a better connector with your spirituality or whatever. So every line had a meaning and the proposition numbers just came out at that time.

JD: Another thing I like, and this might be more Michael than you, is the arrangement, and I’m thinking kind of towards the middle, there’s all this incredible looping, minimalist keyboard cycles going on. In fact, I was first thinking, you know, were you guys influenced by like Philip Glass, Steve Reich and Terry Riley? And then listening to it I’m thinking wow, this is very “Music For 18 Musicians.”

JA: Yeah, well, I love Terry Riley and you know, John Cage and all that kind of minimalistic thing. The idea was always to do “Stepping Stones,” speed it up. And that’s how we did it. And again, Michael added the right things at the right time, and I can’t remember exactly what he did to make it work, but that track opened up. It was interesting if you put a musician like Billy Cobham and Chick Corea, on the track it almost started breathing better.

JD: Mm, so how are Yes fans gonna feel about you playing with a beat box?

JA: World Music hit me very strong in the ‘70s as it did Peter Gabriel. He actually had a label working with world music, and then – I remember a guy, a famous guitar player. I wish I could remember his name, came over and started doing the beat box. Had just been to New York, he said everybody is doing this. [sings a few beats] And I went really? That’s weird. But then it became obviously the thing to do and why not use that.

JD: So, “I Found Myself” is a really lovely song, it sounds like a love song to your wife.

JA: Sure. Yeah, and she sings on it for me. She’s everything that a man could ever wish for. She saved my life on many levels. Taught me what true love is and we’re really very, very happy together, happy wife, happy life sort of thing.

JD: So “Twice In A Lifetime,” that seems a bit of a protest song on one hand and then a spiritual song, but maybe not on the other hand.

JA: Singers sing songs and don’t sometimes feel that they’re singing it right, and they go through depression about not being good enough. And that’s just in general, when I say singer it means everybody. You go through life and sometimes you, you’re doing your song and you’re doing your work and everything’s great, but then it doesn’t feel right and you’re doing the right thing. And and then you look at the news and they’re sending planes with food to save the starving millions. And then you see them sending planes with bombs to destroy, so it, what’s the word for it. The confusion of life is, the politics of life, there’s so much beauty in the world, the earth, music, the nature of life. And yet the politicians are just so greedy and the corruption is so vile.

And this Black Lives Matter is true, we’ve known this for 50 years since I remember Martin Luther King being killed, that whole thing escalated all the times. And then that died down and then it happened again in 1990 – 91 and then it died down again. And now it’s really ramped up, and because we have a very sort of inept misguided president. I’m an American so I can say that without being thrown out of the country… and there’s this time coming of change and I don’t know if Biden can do it. I don’t know who can do it.

JD: So on “1000 Hands” you’ve got a line in there, “Some come to tempt you with visions of the eastern world.” And you say that like it’s not a good thing, and I always thought that you were kind of a scholar, or student of eastern philosophy and spirituality.

Jon Anderson in Zoom Photo

JA: See, it’s only you that will know what is right. There is no harm in understanding that Buddha, Krishna, Mohammad, Jesus were all risen masters. Nothing wrong in that. I think the big wrong that’s been done over the years, terrible, is to say okay, we’re Christian, the rest of you are going to hell. How stupid, arrogant, and actually, you know, not very healthy to think that way, thinking you know, keep everybody else down as Christians are really cool, you know, which is wrong, you know. Collectively we’re all the same, connected the same through our own masters through life.

JD: You give Jean-Luc Ponty a lot of space on that. I think he’s got the biggest solo on the entire album on that track.

29:49

JA: He’s a master. I worked with him and realized that we’re sort of brothers from different mothers. He originates from Brittany. My great grandparents on my mother’s side are from Brittany, so there was this connection right away. I’ve always liked French people. I’ve always liked everything about their world. So I just sent him the track and said – play what you want. And the marvelous thing that he does at the end, how he ties up with Billy Cobham beat for beat, right to the very end. He sails. He actually has this very mystical, magical way of playing the violin. It’s very beautiful.

JD: Absolutely. It also has that chorus toward the end, which is really great and very anthemic. Did you generate that?

JA: Yeah, the whole thing was recorded and written in Big Bear exactly the way it was produced. It’s just the addition of Billy Cobham, Chick Corea, and then a choir, and of course, Zap Mama in there. The mysticism of my work is right on the money on that track. It’s just whew, okay, that works. And it was exactly where I was at Big Bear. I was there with a wonderful friend of mine, Keith Hefner, a keyboard player. And I’d just say I want to hear some big chords, but very open. And he did, and I demanded: keep doing more and do some more. You know, the suspended chords, something like that. And off he went, and that was the ending and it was all this choir was in there. It’s very glorious, the sound of heaven in that state of mind, you know.

JD: So where does the music come from? I’m not sure you actually found the answer to that. Did you find the answer to that? Is it a prior lifetime, is it something bigger?

JA: You know, I wrote a story with my wife about 10 years ago about this bird singing a song, and I realized all birds sing a song and interact with each other, inter-react with each other, and all the sounds of the wind, and the flowers and everything all keeps the world going. And then something happened, this rain came, a deluge of rain, so everybody went under this big tree. And these squirrels that live in the tree got very upset with all these birds making the noise in the morning and started throwing nuts at them, hazelnuts. And one of them hit the little bird, Tula, and she forgot her song. And in that moment the world stopped because the song had stopped. And the only wise animal in the tree was this big bear, and he said, “Tula, come with me. I’ve got to go to The Big Cheese in the moon.” So they went to the moon and The Big Cheese thought he knew everything, but he didn’t know where music came from. And he thought wait a minute, I’m The Big Cheese, I’m supposed to know where music comes from. Ahh, you’ve got to go to the Pleiades, so they went to the Pleiades and that’s where music comes from. And Tula learned a new song, brought it back to Earth and changed the world with a new song.

JD: So in a way you didn’t answer that question then, right? That’s where Olias was born.

JD: Why the Pleiades?

JA: The seven sisters, I don’t know, it just sounds perfect.

JD: You’ve played with some interesting people, besides your actual bandmakes who are also really fantastic musicians. Kitaro, are you still in touch with him?

JA: I haven’t seen him for many years. He used to live in Boulder, CO up in the mountains, so I went to see him there. I’d seen him do a show. We met. He wanted me to sing on his album. I thought that’d be great, and I sang on a couple of songs for him, thinking we would make an album together, like I do with Vangelis. We spontaneously create music together. It’s a very magical thing to do. And we toured quite a bit in the Far East as well as a few gigs in America.

And it was a wonderful experience, but there wasn’t this obvious connection, because I went to see him in his house in Tokyo, well, in the mountains of Japan there. And we tried to come up with some ideas together for two or three days, and nothing happened. I think we were friendly with each other, but we didn’t have a spark like I had with Vangelis, a spontaneity. I’m very easy to write with. I’m very open to write with, as I did with Steve Howe and Chris and Rick and Trevor and everybody that I’ve worked with, but with Kitaro, he’d always say yes about everything, and I learned later that most times Japanese people don’t like saying no.

JD: That’s true, actually.

JA: Sweet guy.

JD: He’s not a collaborative musician, I don’t think.

JA: No.

JD: I think if you look at the span of his, his work, he was in a band once for a while, the Far East Family Band, and then he was solo. And I think he’s much more of an Olias guy except he needs other people to do it live.

JA: True. You know, in some ways I’ve met many musicians and never made music because you can sense it’s not gonna happen. But I do remember meeting Lamont Dozier from the famous Holland Dozier Holland, as I was making an album called In the City of Angels. And I just went to see him. I was introduced to him by the producer, and he was living in the valley. And we did four songs in two hours and he was brilliant. It just like [snaps fingers], here you go, songwriting. “Hold On To Love” was one of the songs we did, really good song.

JD: Vangelis: are you still in touch with him at all?

JA: No, it’s interesting that Vangelis had a conniption. I don’t know if you know that word?

JD: Yes.

JA: We did four albums together and through very, very bad management, I was told–this is in the ‘80s when I was pretty famous at that time with 90125 and everything. And the record company wanted me to help finish the album and add another song, and I said – “Does he know about this?” “ Oh, yeah, Vangelis told us to tell you yes, another song would be helpful.” “Oh, okay”… Not thinking, you know. I just got on with helping to reproduce the album a little bit, add little bit of sound effects here and there. And I didn’t know. I just thought he’d understand this was what he wanted to do or whatever. But he sent me a very–in the old days, what was it, not an email.

JD: Fax?

JA: Fax, fax. He sent me a fax and it was actually a fax written by his righthand man, who never really took to me as a person, I don’t know why. And it was a very angry fax, how dare you tamper with my production, etc., and some very, very typical English expressions, not Vangelis at all. So what I did, stupid that I am, I underlined all the, all the bad lines about all the things that I’d done wrong, and I wrote at the bottom, I’m so happy you like it! You obviously don’t do that to a Greek person because he never spoke to me again.

JD: But tell me, in terms of musicianship, he’s like unbelievable, isn’t he?

I’ve been like sitting next to him and having him play, and he just whips it out.

JA: He’d do a symphony every day. And then somebody asked me the other day, what was my favorite song with Vangelis? And I remembered the recording of “Friends Of Mr. Cairo.” The way we worked was very spontaneous. We’d have lunch together, and then we’d go the studio, which you’ve been to. And he’d have the mic on and he’d play and I sang, and we did two minutes of that, a minute of that vibe, three minutes of this vibe, and a minute of that vibe. Spontaneous singing ideas. And then we edited together and came up with “Friends Of Mr. Cairo.” And I started to listen to what I was trying to sing, and I learned–I was thinking about The Maltese Falcon and how you know, in the 1930s, the gangster movies, who financed them? Of course, the guys, Al Capone and all that, they financed the movies. They wanted the street cred, you know. And the ending was very different because I said can you play a little piece because we’d actually edited together our work, but the ending didn’t kind of sing properly. So I said can you play like a Douglas Fairbanks silent movie? And right away he just played it, you know, without question. And I sang about the silver screen and everything. And I said well that’s, that took us like two hours, three hours to make, and he said a great piece of music. It’s a visual–he said all we need to do is get maybe people, somebody who can, you know, speak just like Peter Lorie or Bogart, or Sydney Greenstreet. And we got this guy to come in and do the overdubs the following day.

JA: He’d do a symphony every day. And then somebody asked me the other day, what was my favorite song with Vangelis? And I remembered the recording of “Friends Of Mr. Cairo.” The way we worked was very spontaneous. We’d have lunch together, and then we’d go the studio, which you’ve been to. And he’d have the mic on and he’d play and I sang, and we did two minutes of that, a minute of that vibe, three minutes of this vibe, and a minute of that vibe. Spontaneous singing ideas. And then we edited together and came up with “Friends Of Mr. Cairo.” And I started to listen to what I was trying to sing, and I learned–I was thinking about The Maltese Falcon and how you know, in the 1930s, the gangster movies, who financed them? Of course, the guys, Al Capone and all that, they financed the movies. They wanted the street cred, you know. And the ending was very different because I said can you play a little piece because we’d actually edited together our work, but the ending didn’t kind of sing properly. So I said can you play like a Douglas Fairbanks silent movie? And right away he just played it, you know, without question. And I sang about the silver screen and everything. And I said well that’s, that took us like two hours, three hours to make, and he said a great piece of music. It’s a visual–he said all we need to do is get maybe people, somebody who can, you know, speak just like Peter Lorie or Bogart, or Sydney Greenstreet. And we got this guy to come in and do the overdubs the following day.

That was the most exciting time with Vangelis. They were always the first take.

JD: Really?

JA: Every song we did together was the first take, then we’d either keep it or edit it and join it with another first take, and he would do his production, and I’d be learning my lyrics, what I was trying to sing. And within a day we’d write two songs. And I did the vocals, whew. It was the opposite to my work with Yes. And that was the joy of looking at Vangelis as my mentor. He taught me so much, I can’t express how deep I feel about his, I loved him. I love him, of course I do. And I’m ever grateful for being able to–I mean the funny thing was that I sang with him on his first album he did in London, was Heaven and Hell. And I sang a song which the record company really wanted to release as a single. I didn’t want to get into that world, pop song, you know, it’s just a lovely song. And I heard that after I worked with him, he tried out four other guys to do the same thing. And he couldn’t get them to sing like I do, or think of lyrics like I do, but he did try…said what do I need Jon Anderson for?

JD: So why, why did he call you in in the first place on Heaven and Hell? What had been your connection or was there any?

JA: Because I tried to get him into Yes, because we’d just done a long, long drawn out tour. And Rick Wakeman was so unhappy. We did the tour, Topographic Tour, and it was hard work on many levels. Rick just didn’t enjoy it and you could sense it on stage, and then he left the band. And I’d just been given this record by a friend of mine in London, called Creation du Monde (song from the album L’Apocalypse des animaux) by this guy Vangelis. And I took a deep breath and went to Paris. Got his phone number and called him up, and said you know, would you like to work with the band? Okay, yes, I could do that, yes. So he packed up his Daimler and his equipment and drove to London. And we looked after him for a couple of weeks but it just didn’t work with Yes because he’s too spontaneous and couldn’t get into the repetition of learning parts. Where Yes was very clinical, trained, training itself to be aware of each other’s parts, you know, like a band does.

So Vangelis stayed on, got a studio as you’ve been to it, in New Marble Arch, and we just kept on being friends. And I worked on some music for Heaven and Hell, his first solo album in England, and I just signed once we did “Run,” “How We Chased a Million Stars,” and “Touched As Only One Can.” That’s, that was about us.

JD: Wow, can’t believe you can pull that up after all these years ‘cuz I’m sure you’ve, you’ve never done that live or anything, right? But it’s interesting what you said, because he is – this is not a criticism of Yes – Vangelis is very much an in-the-moment musician, whereas, whereas Yes was…

JA: Just the opposite. You know, it was just, in as much as you have an orchestra, you have everybody reading dots. You know, how do they do that? How? I still don’t know how they do it, but they do it. And now I’m working on some songs that I wrote 40 years ago, and it was orchestrated by a friend of mine in Holland. And he just sent me the midi files, so I’ve got the midi files here now. And now I’m doing a 21st century version of this music that I wrote 40 years ago, symphonic. So symphonic with choir.

JD: So “State of Independence,” that was an amazing song and certainly one of the signature songs that you two did together.

JA: Yeah, that, that happened in a very interesting way because I was traveling back to Paris from working in L.A. And heard that Vangelis was in the studio, so I, I rang the studio and said yeah, he’s still here. So I went over to the studio and he was just playing on the keyboards. And I, I waved and said is the mic on? He said oh yeah, yeah. And for the life of me, I sang that song all the way through lyrically, 90% perfect, one go, one take.

JD: Were you making up the lyrics?

JA: Yeah.

JD: No!

JA: It was spontaneous. It was really that spontaneous moment that you dream of because after a while working with Vangelis and working with Yes, there were times when I actually wrote the lyric as I sang it, almost, you can hear it. I’ll be singing ideas and I know what I’m thinking. And if I listen, listen closely, I’m actually singing the right words, just now and again losing my train of thought…and just need to be, change that last word and uh you know.

And that’s the way I’ve been working ever since that. I go for it, and never sit down and worry about lyrics or write them over and over. I’ll just go for them and let go of them, and say there they are. And that state of independence, like oh my gosh.

JD: Okay. Okay, I have to ask you the obligatory yes question, so what’s up, anything, nothing?

JA: Everything and nothing. As far as I know, I would be very excited to get together with everybody, and I mean everybody and put on a show. And I don’t want any involvement in terms of management. It should be done from the musician’s view with a good promoter. Just keep out of the way and let me get on with it.

JD: You did get Steve Howe on the track “Now and Again.”

JA: Yeah. I had a feeling we were going to finish the song with the third verse of “Now” and Michael Franklin added some beautiful arrangement there. And I said this is finished now, but I’ve just got to ring up Steve and get him to play on it at the end because I played on an album of his, Bob Dylan songs, a few years ago and I thought hey, he owes me, and he does. So we got in touch and you know we love each other like brothers, and we’ve been through the highs and lows of life together. And he played a beautiful acoustic guitar on that track and right away I started singing and I sang about us and how we worked together and the music we made together reached so many people and it’s good to do it again.

The End