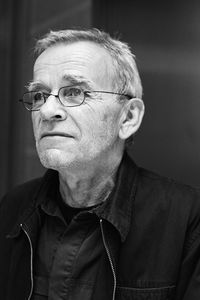

Dieter Moebius, Electronic Pioneer, Switches Off

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Dieter Moebius: 1944-2015.

In the world of progressive space and ambient music, the German group called Cluster were eccentric wizards, musical alchemists who defied traditions, even the ones they helped create during the space music days of 1970s Berlin. Hans Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius have released dozens of albums as Cluster, and under their own names, over the last 45 years.

Cluster influenced three generations of ambient composers, beginning with Brian Eno and continuing through Robert Rich, The Orb, Ulrich Schnauss and countless others. Although they were lumped in with the space music of Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk in the 1970s, Cluster always followed their own path, creating sonic landscapes that could be quaint and spacey, like a surreal music box slightly sprung, or they could assault the walls of dissonance.

Now, one half of this influential band has flipped the off-switch for the last time. Dieter Moebius died on July 20 at the age of 71. I first met Moebius in 1982 in his Berlin apartment where I was interviewing him for the radio series, Totally Wired: Artists in Electronic Sound. Moebius was a gracious, shambolic host, offering us food and weed in equal doses. He had a friend there, who might have been Gerd Beerbohm, his collaborator on a couple of albums. The interview wandered down many paths revealing Moebius as a music omnivore as he joyfully recounted tuning in John Peels’ radio show on the BBC. We wound up never using that interview because it didn’t quite reach a state of coherence.

The two members of Cluster were like the zero and one, yin and yang. Roedelius is a tall, gregarious man who seems like everyone’s favorite grandfather. Dieter Moebius was the perfect foil, small and quiet with a wry sense of humor.

Although they are considered pioneers of electronic music, when Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius got together with Conrad Schnitzler in 1969 as Kluster, there weren’t a lot of synthesizers around. But they already had a slightly different vision of music so they used whatever was at hand.

“There were synthesizers but they were way too expensive,” lamented Moebius in a 1997 interview. “In the beginning we had drums and all kinds of cellos and all kinds of things that we picked up.”

“We started by using our instruments such as violins, cello, guitars, and flutes, electrified,” added Roedelius, who turns 81 this October. “Also very different stuff like alarm clocks, woods, metal, and our voices and percussion, we used everything: Cooking pots, cups, glasses, water drops, vases, wood, metal”.

https://youtu.be/QAMIgrAhELs

In the beginning, even though Cluster used acoustic sound sources, they manipulated these signals in the same ways a synthesizer would.

“In a way it was a synthesizer we created with our instruments with pick-ups,” revealed Moebius, “because we would send this signal, this sound through a wah-wah pedal or phase-shifter. That’s like in a synthesizer with the filter stuff and all these things. So we each had our own synthesizer made up with our possibilities.”

They eventually did adopt conventional synthesizers, but in their hands, they always sounded like something they had cobbled together on a workbench. Schnitzler left the group and they changed the “K” to a “C” for Cluster. In the early 1970s, they found themselves at the heart of the burgeoning space music scene in Germany, alongside Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Kraftwerk, Ash Ra Tempel and Popol Vuh. Most of the music emerging from this scene was surreal, electronically-charged and awash in hallucinogenic and space imagery. Moebius said that these sounds reflected the mood of the city at that time.

“It was quite a chaotic time in Berlin,” he remembers, “Perhaps that’s why we made the decision to make it loud and strong and a machine sound, because of the police running around the streets every day, woo, woo.”

Although they were there at the genesis of the Berlin sound, the music Cluster made bore little resemblance to Klaus Schulze or Tangerine Dream.

“No, we have different backgrounds,” explained Roedelius, who is older than most of the musicains on that scene by more than a decade. “My family, in the past, my ancestors were teachers and preachers and people who had very much to do with spirituality and also with music. They were cantors and organists and all of that in church so, I think I got my roots back then.”

“We didn’t care about what the other people did really,” boasted Moebius. “We met them all the time.”

“And know them still,” adds Roedelius.

“But theses friends of ours were thinking more commercially than us,” said Moebius proudly. “We never thought really commercial. That’s perhaps also the difference. You can hear it in the music in a way.”

In 1976 as well as 1996, Cluster didn’t play their instruments so much as coax sounds out of them. A strange whirr collides with a muffled drum, a distant piano fights its way out of a thick electronic fog, and lush strings encounter industrial rhythms.

In 1976 as well as 1996, Cluster didn’t play their instruments so much as coax sounds out of them. A strange whirr collides with a muffled drum, a distant piano fights its way out of a thick electronic fog, and lush strings encounter industrial rhythms.

Ironically, thirty years down the road, Cluster’s music still sounded like it could’ve been made in someone’s kitchen. They use modern synthesizers, digital samplers and computers but their music still sounded like a sprung music box on their 1997 album, One Hour. But like a music box, it has a certain timeless charm.

Cluster is frequently cited as being the fathers of ambient music, a reputation that partly arises from a pair of albums they recorded with Brian Eno in the 1970s. You can hear the influence of each musician on the other with Eno’s Before and After Science and Cluster’s Sowiesoso. The Cluster-Eno pairing looms large in their mythology, but for Roedelius and Moebius, it was a brief moment.

“He knew more about the instruments and studio than we did at that time,” recalls Roedelius. “Of course he was working at that time with David Bowie in the studio and he was working on his own solo project, Before and After Science.”

They initially got together at an informal jam session during recordings with Roedelius and Moebius’ other project, Harmonia, which included guitarist Michael Rother.

“Our first real session was 76 when we worked together with Michael Rother from Neu!,” says Roedelius. “Then Brian came to our studio and we sat down for one week and played together and put it down on tape and it worked like we work always sitting together and doing it and just listening to it and saying yes or no.” Some of those earlier recordings came out in 1996 on the album, Harmonia ’96.

Eno brought a precision to their recording methods that was new for them.

“I learned a lot from him because to be a bit more organized in a way,” admits

Roedelius.

“Yeah. He was really good organizer” agrees Moebius, slightly tongue in cheek.

“I think he still is and that’s the reason why he’s so successful because he is so well organized,” continues Roedelius. “But in a way we stayed the way as we did. We just behaved a bit more concentrated in our work after.”

“For one week,” concludes Moebius dismissively.

Many people think Cluster’s music changed after their encounter with Eno.

“No,” Moebius quickly disagrees.

“It changed the work of Brian Eno,” boasts Roedelius. “It’s the other way around.”

Cluster’s music still speaks to later generations, including Alex Paterson. As the mixmaster of ambient superstars, The Orb, he’s probably sampled his share of Cluster albums.

“It’s a compliment to them in their own way,” he says, defending his appropriations. “It’s also a shame that people never heard things like that before. And again it takes people like ourselves to turn around and say, ‘Well look we made music being influenced by these types of people.’ But none of them people know what we are talking about. ‘Who in the hell is Cluster?’ said a lot of people.”

Maybe some people said that, but Robert Rich cites them as an influence as does their fellow German, Ulrich Schnauss, who was only a baby in 1977, at the height of Cluster’s influence. One of his songs, “One Finger In Someone Else’s Chords,” from his collaboration with Mark Peters of Engineers, was consciously influenced by Cluster.

“This is one of the songs on the album that took the longest time,” said Schnauss when he visited the Echoes studio in 2013. “And when it actually started working it did work because we put that humorous element in. And that’s obviously something that’s a trademark of the Cluster sound. It’s humorous, but not in a cheesy way, more like in a quite warmhearted and empathetic way.”

Cluster was pleased by the recognition they were receiving later in their careers when people started calling them the “Godfathers of Ambient Music”.

“Yes, I mean for me it was very new to learn about this that we are kind of fathers for this scene’” says Roedelius with surprise. “Also because it developed in so many directions and it’s so varied. Some is really boring and hard to stand and hard to listen to, and some is really very nice. But we always did what we did and didn’t care about what other peoples did with it.”

Moebius is less sanguine. “I think all the good stuff that’s happening now, they got it from us,” he laughs, even though I suspect he was serious.

Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius continued to make music right up till the end. The last Cluster album was Qua in 2009. The two separated in 2010, but live albums continued to be released throughout this decade. Moebius’ final solo album is Nidemonex on which he continued to create fractured sounds for fracturing skulls. Roedelius has been recording as Qluster with another musician.

Dieter Moebius came from a time when experimentation was hard work and invention was the mode of the day. Failure was an accepted outcome and music was meant to be challenging. Throwing conventions to the winds, along with kitchen utensils and anything else you could gather, was standard procedure. If anything, Cluster returned to an even more experimental sound in their later years. Now, another light from an era has passed.

~ John Diliberto with contributions from Jeff Towne

Thanks, John and Jeff, for the fine retrospective. Moebi was one of my favorites – as a friend and musician. As fantastically wry and sardonic as he could be, he was also one of the kindest, warmest and most generous – I think his music was so vital precisely because of this unlikely combination. We lost a good one.

This is music that has been/is ignored AND massively borrowed from. Beautiful and strong at the same time. I would attempt further explanation but the last paragraph of the article says it all. Thanks Moebius for the years of hard work and dedication, most of all for the enlightenment of the music.