Brian Eno's Lament for The Earth: FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE, Echoes November CD of the Month

by John Diliberto 10/31/2022

The avatar of ambient, Brian Eno, also has a song side to his releases. His first three solo albums were all vocal releases and he’s scattered them in amongst his ambient works over the last five decades. FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE is a predominantly vocal work but unlike Eno’s other releases in the oeuvre, I have to admit, I had a hard time wrapping myself around it. I do love Eno’s previous song work which has ranged from the manic insanity of “Baby’s On Fire” to the wistful yearning of “Golden Hours,” the deep psychological dive of “Under,” and the haunting lament of “And Then So Clear.”

I had to let go of preconceptions and expectations because FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE is different. There are no beats, choruses or hooks. Instead, he surrounds these songs of both hope and doom with beat-free, oscillating landscapes of squiggly synths and deep rumbles, distorted guitar and mysterious shudders. Longtime collaborator, guitarist Leo Abrahams, plays guitar and is credited with post-production. He’s likely responsible for the dissonant, atonal aspects that make FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE seem so foreboding. “Garden of Stars” in particular is a descent into the abyss instrumentally and vocally. But lyrically, Eno suggests we are all made of stars.

On FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE , a title which foretells the music within, Eno has cast a hymnal warning of a world that is fading. Those who follow Eno closely are aware of his involvement in human rights, environmental and political issues. Among those movements, he was co-founder of the Long Now Foundation, which was created to think in longer time terms about the earth. Among his involvement was the Clock of the Long Now.

On FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE , a title which foretells the music within, Eno has cast a hymnal warning of a world that is fading. Those who follow Eno closely are aware of his involvement in human rights, environmental and political issues. Among those movements, he was co-founder of the Long Now Foundation, which was created to think in longer time terms about the earth. Among his involvement was the Clock of the Long Now.

While Eno has looked for solutions to our terminal case of self-destructiveness, much of FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE seems to be about lost causes and questioning our very existence. On “Who Gives A Thought,” he begins each of the three verses with that question. “Who gives a thought about nematodes”, “about fireflies,” “about laborers” he intones. On “Icarus or Blériot,” he asks whether we are like Icarus flying too close to the sun or early 20th century French aviator Louis Blériot, who was the first to fly across the English Channel.

The song “We Let It In” is centered by long human exhalations, that could be a sound of life or a death rattle. His daughter, Darla, intones a looped chant to the Sun while Eno praises that star in a voice that sounds like someone remembering something long past, reflecting on its impact on life, now gone.

On tracks like “There Were Bells,” he goes deeper into his lower range than ever before. This was the first single off the album. It opens with a long ambient meditation of electronic bird sounds and synth pads. Eno’s voice comes in like a descending angel. Deep and yearning, the first two verses extoll the majesty of the world.

There were bells above that rang the whole day through

And the sky was shot with light and hazy blue.

But the third and final verse takes an apocalyptic turn.

There were horns as loud as war that tore apart the sky

There were storms and floods of blood of human life.

Eno sings these songs like he’s holding onto a lectern for dear life, waiting for the world to end.

“These Small Voices,” co-composed by Jon Hopkins who also plays piano, features a choral sound reminiscent of Shape-Note Singing. Eno is joined by singer Clodagh Simonds (of Mike Oldfield’s Ommadawn) in creating the choir that sounds this hymn to the end of life.

There are two instrumental tracks on the album. “Inclusion” is a gentle ambient chamber work with Marina Moore playing viola and violin. Eno and Abrahams surround it with a deep synth pad and space squiggle giving it an unsettling nature.

The last song on the album, “Making Gardens Out of Silence in the Uncanny Valley,” goes nearly 14 minutes long. It is pure ambient Eno, and while it features singer Kyoko Inatome, her words are electronically distorted and stretched to be unintelligible. Like the Earth that this album is lamenting, it revolves slowly, textures, synth pads and sound effects wafting through in slow motion, finally ending with the electronic bird sounds that featured on “There Were Bells.”

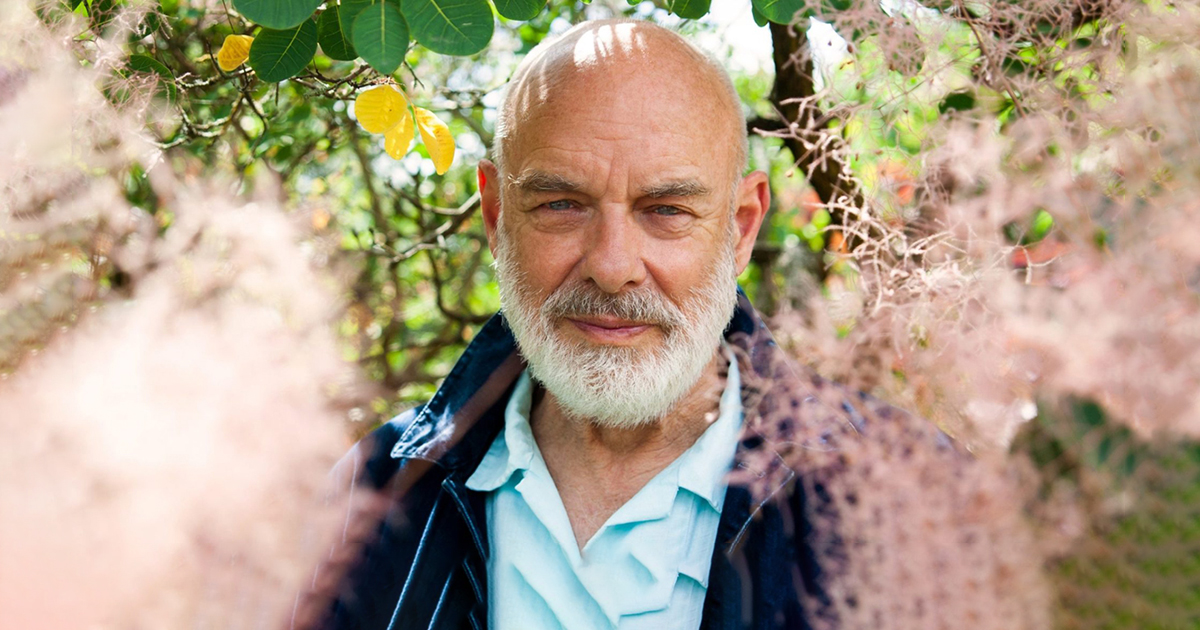

This is the sound of a 74-year-old man who is closer to the end of life than the beginning and observing what may be left for his children. Brian Eno sees the beauty on the planet, and laments what is happening to it. It’s his most personal album ever. His voice, usually without much processing, is naked front and center. FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE is not the easiest album to embrace. You need to live with it, and see how deep from Eno’s heart it emerges.