The Aniversary of an Ambient Space Masterpiece: Klaus Schulze's Mirage at 40.

Written by John Diliberto on April 26, 2017

Klaus Schulze’s Mirage featured tonight on Echoes 4/26/2017

How many nights did I listen to Klaus Schulze’s Mirage? Lights out, stereo cranked up, head placed at the perfect listening spot. The answer is many. Mirage came out in the days when you would actually sit and listen to compositions that stretched to 30 minutes long, and then flip over the record to hear another one that was also 30 minutes long. And that’s what Mirage had, just two masterful compositions, “Velvet Voyage” and “Crystal Lake.”

How many nights did I listen to Klaus Schulze’s Mirage? Lights out, stereo cranked up, head placed at the perfect listening spot. The answer is many. Mirage came out in the days when you would actually sit and listen to compositions that stretched to 30 minutes long, and then flip over the record to hear another one that was also 30 minutes long. And that’s what Mirage had, just two masterful compositions, “Velvet Voyage” and “Crystal Lake.”

Klaus Schulze was in the thick of 70’s German electronic music at the time when Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Cluster, Neu! and Can were all experimenting and discovering their sound. He was a member of Tangerine Dream, playing drums on their 1969 debut album, Electronic Meditations. He then formed Ash Ra Tempel (now Ashra) with guitarist Manuel Göttsching and recorded a couple of albums with them. But Schulze heard a different sound, one that was expansive and immersive, a sound that suggested alien landscapes like those of the Urs Amann covers that adorned his early releases. It also suggested altered states of consciousness. Of course, they were all doing that in LSD-induced states of mind. (See Cosmic Jokers).

In April of 1977, Schulze released Mirage, his eighth album in five years and while it had a more subdued energy and none of the driving sequencers of his previous work, Body Love and Moondawn, it does call back to his first two albums, Irrlicht and Cyborg, which were more inspired by Ligeti drones and string-like textures than trance rhythms. On Irrlicht he even had an orchestra that he recorded with one microphone on a cassette. Schulze himself just played an electric organ on Irrlicht and added a synthesizer for Cyborg.

In April of 1977, Schulze released Mirage, his eighth album in five years and while it had a more subdued energy and none of the driving sequencers of his previous work, Body Love and Moondawn, it does call back to his first two albums, Irrlicht and Cyborg, which were more inspired by Ligeti drones and string-like textures than trance rhythms. On Irrlicht he even had an orchestra that he recorded with one microphone on a cassette. Schulze himself just played an electric organ on Irrlicht and added a synthesizer for Cyborg.

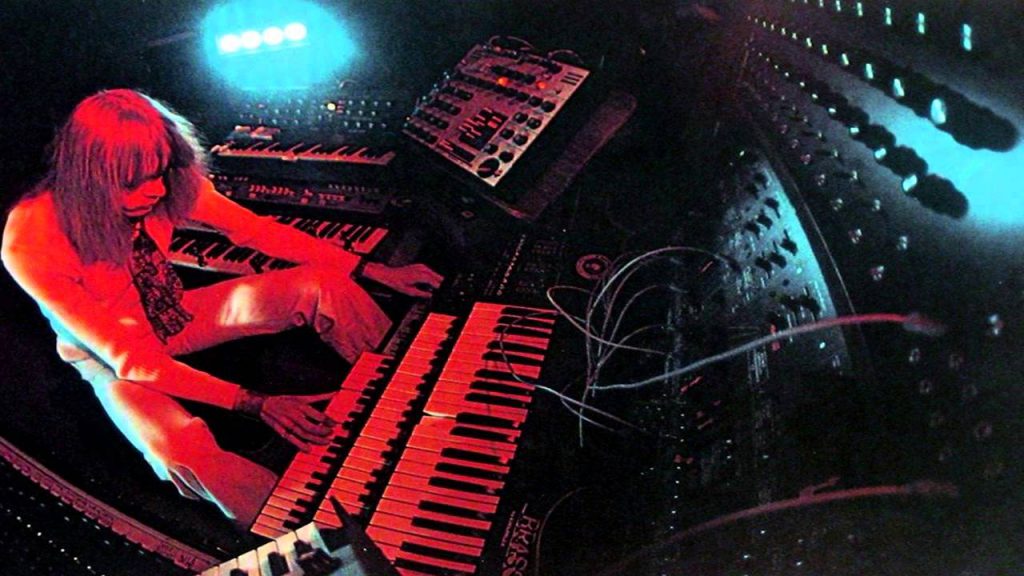

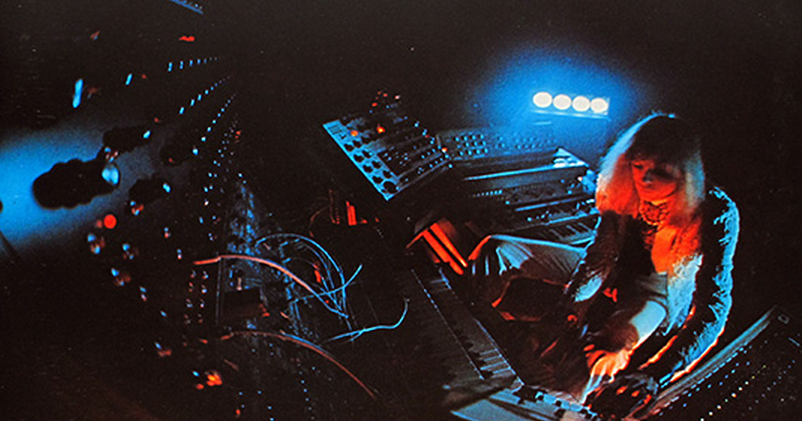

That sound is reflected on the opening side, “Velvet Voyage,” but with substantially better equipment and much more of including ARP Odyssey, ARP 2600, 2 Minimoogs, Micromoog, Polymoog, Moog Modular, EMS Synthi A, Farfisa String Orchestra, Farfisa Professional Duo Organ, 3 Crumar keyboards, 2 PPG Synthis. Just, you know, to name a few.

Although Schulze and Tangerine Dream had recorded drone works, “Velvet Voyage” was the first landmark drone-zone piece of the modern era. It opens with the sound of siren whales, as if it picked up from the middle of Pink Floyd’s “Echoes.” An undertow of synths arrives like the climactic scene of 2001. Schulze cross fades and overlaps long, thick chord sequences as ghostly mellotron choirs flow into the work. You expect someone to chant “bring out your dead.”

In fact, Schulze claimed in the liner notes to the 2005 reissue, that much of this album was composed while his brother was dying, which may account for the somber, funereal mood. As the piece evolves, modalities change. The synths move into a major key, string pads seem to soar and subtly, a low bass pattern emerges, pushing the work forward in a slow evolution.

Bell-like sequencer patterns emerge that foreshadow the other composition on the album, “Crystal Lake” and slowly, Schulze begins soloing, probably on the Mini-Moog. It was his solos and modal forms that always made me think of him as the John Coltrane of electronic music. Like most Schulze works, it builds to a crescendo, albeit a muted one, before dissolving back, the bell like sequence returning, pinging across the stereo spectrum.

The second side is kind of the “hit” of the album, “Crystal Lake.” It echoes the sound of Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians.” Although that composition premiered in 1976, the album wasn’t released until 1978, a year after Mirage. The more likely influence was part three of Steve Reich’s “Drumming” which came out in 1974. Like Reich’s work, Schulze deploys cyclical patterns on “Crystal Lake,” mirrored through delays and sequencer loops. It’s the track that lives up to the subtitle of Mirage: A Winter Landscape. This has been a recurring track on Echoes winter season shows from the beginning.

The second side is kind of the “hit” of the album, “Crystal Lake.” It echoes the sound of Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians.” Although that composition premiered in 1976, the album wasn’t released until 1978, a year after Mirage. The more likely influence was part three of Steve Reich’s “Drumming” which came out in 1974. Like Reich’s work, Schulze deploys cyclical patterns on “Crystal Lake,” mirrored through delays and sequencer loops. It’s the track that lives up to the subtitle of Mirage: A Winter Landscape. This has been a recurring track on Echoes winter season shows from the beginning.

My image of Mirage has been shaped by a comment made by electronic musician Mark Shreeve of Redshift. In 1983, he described Mirage as if it had “formed out of thin air, untouched by human hands.” You can hear that immaculate sound in “Crystal Lake.” The sequencer patterns seem to appear in mid-air, spinning in interlocking cycles that remind me of the Omega Molecule in Star Trek: Voyager. (Sorry, I’ve been revisiting that show recently.)

“Crystal Lake” builds on its sequences, laced by siren synth lines that phase in and out of deep space. The track dissolves at 17 minutes in, fading into textures similar to “Velvet Voyage,” creating a circular connection between the tracks that would make a perfect loop.

Each of the two tracks on Mirage has multiple subsections with titles like “Eclipse,” “Lucid Interspace,” “Chromewaves” and “Liquid Mirrors.” They are actually pretty good descriptive titles you can hear as the compositions slip into those movements.

Mirage was reissued in 2005 with an additional bonus track, “In cosa crede chi non crede?”. Surprisingly, given it was his eighth album, this masterpiece wasn’t even the pinnacle of Klaus Schulze’s recording career. Albums like X, Trancefer and Audentity would follow. Until recent health issues slowed him down, Schulze has remained creative well into his sixties. He turns 70 on August 4.

Among space music and Berlin school acolytes, Klaus Schulze is a God, especially to that 80’s generation of electronic musicians like Steve Roach, Robert Rich, Michael Garrison and Mark Shreeve. But out in the world, Schulze is rarely mentioned. Can, Neu!, Cluster and Kraftwerk are always the the ones cited, especially by younger musicians. Jean-Michel Jarre and Vangelis get occasional love and Tangerine Dream is grudgingly acknowledged, but in the “real” world, you rarely, if ever, hear anyone who began making music in the 90s and beyond, mention Klaus. Spin them some Mirage and that might change. It is was a landmark work in which Klaus Schulze movedinto textural, hallucinatory space, music made for out of body experiences. Those weren’t Schulze’s stated aspirations. That’s just what happened to anyone who listened to it.