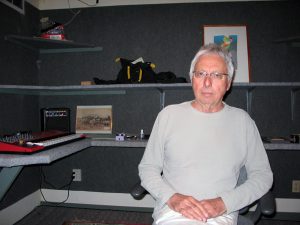

Harold Budd's Quiet World. An Ambient Avatar Turns 80.

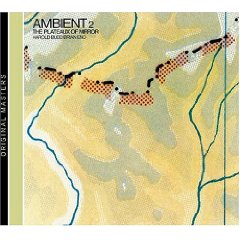

Harold Budd is a legend in the ambient world, but like his music, he’s a subtle legend, known probably more among musicians than fans. His early 1980 albums with Brian Eno, The Plateaux of Mirror and The Pearl, are among the early signposts of ambient music. Older artists like Tim Story and Ruben Garcia genuflect at Budd’s altar, while a new generation of composers including Balmorhea, Lights Out Asia, and Nils Petter Molvaer have been influenced by his work. His collaborators have included Andy Partridge of XTC and guitarist Bill Nelson.

Harold turned 80 on May 24, so I thought it would be a good time to go back to his feature as one of 20 Icons of Echoes from our 20th anniversary which I’ve updated.

“Playing in a club, home at four o’clock at night and it’s like, really, you’re wasted and then I put on some Harold Budd,” fondly recalls Norwegian trumpeter Nils Petter Molvaer. “I just went into this state of mind where I could sleep. It’s the way I still listen to it, actually.”

“I like Harold Budd’s music a lot,” reveals classical composer John Adams. “He’s pretty pretty but there’s a certain just a quality to it that isn’t shlock.”

Peter Gabriel producer Daniel Lanois remembers his first encounter with Harold Budd’s music. “I had this image of a very strange, big Paul Bunyan guy who played like feathers on the piano,” he chortles.

Born on May 24th, 1936, Harold Budd has that laid back demeanor of a golf pro. He started out as a jazz drummer in the 1950s, then after a stint in the service, he went to college and started composing. A student of avant-garde jazz and Schoenberg style serialism, Harold Budd revolted and began making what he rebelliously called, “pretty music.”

“I will tell you at the time to use the word ‘pretty music’ was kind of a political statement,” Budd divulges. “It was against the received wisdom of what avant-garde music was at the time which was confrontational and purposely without…ugly is what I call it. I just wanted candy. I was not expressing my inner being. I was just not doing anything except trying to make it as devastatingly pretty as I possibly could.” He did that on recordings like Pavilion of Dreams, an album of such sublime beauty that few have equaled.

Although Harold Budd’s music is usually based around the piano, he doesn’t actually have one in his Los Angeles home.

“The piano is aesthetically awful,” Budd states bluntly. “It is an ugly thing. I learned how to play it if that is what you want to call what I do out of self-defense really. There was no way I could adequately notate my intentions.” That may be because Harold Budd’s music doesn’t translate to notes on a page. It’s what’s between the notes, the silences, the decays, his response to echoes and effects that make his music so powerful.

Brian Eno recalls how Budd’s intuitive approach interacted with his own electronic treatments on their second album together, The Pearl. “Yes, it is actually a technique that I really learned from working with Harold Budd fondly enough,” he recalls. “Because with him I used to set up quite complicated treatments and then he would go out and play the piano. And you would hear him discovering, as he played, how to manipulate this treatment. How to make it ring and resonant. Which notes work particularly well on it. Which register of the piano.”

Plateaux of Mirror and The Pearl remain signpost works of Harold Budd and prevented the musician from experiencing what would likely have been a shy and retiring career as an academic composer. Instead, he was simultaneously thrust into the worlds of contemporary classical music and art rock. He’s collaborated with Andy Partridge of XTC, the late music auteur, Hector Zazou, bassists Bill Laswell and Jah Wobble, and Cock Robin guitarist Clive Wright. Their first impressions of Harold Budd’s music was probably similar to that of guitarist Robin Guthrie who has been recording with Budd since the 1980s.

“I thought it’s really slow isn’t it?” says Guthrie, still best known for his work with The Cocteau Twins. Guthrie and Budd have gone on to record film scores and albums together, including the diptych, After the Night Falls and Before the Day Breaks.

Harold Budd often works from a metaphorical base. He’s always written poetry and began recording it on his album, By the Dawn’s Early Light. Even his titles are poetic. In 2009, sitting at a piano at Knobworld Studios in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles, Harold Budd opens up a small notebook.

“I always have a notebook with me,” he discloses. “I write down song titles the way that I sketch out poetry ideas, or something like that, yeah.” Often those titles create a psychological space that Budd inhabits in the music like his composition, “The Room of Forgotten Children.”

“The room with forgotten children,” begins Budd. “There was no such thing. I did not know what it does. To me it triggers a certain sense of loss and a kind of poignance in a way seems attractive. Not unlike some of the black and white images in some of Jean Cocteau’s films. They are very distant and somewhat unsettling but a little bit wrong in a way. That is a nice idea.”

A bout of depression in the mid-2000s led to Harold Budd’s retirement, but that proved to be short-lived. Even as he hits his 80th birthday, Harold Budd is still creating music of mood and melancholy where less is sometimes more.

“I’m not really a musician,” he candidly confesses. “Or in so far as I am a musician, I’m not a well-rounded one. There are very few things I can do as a musician. The one thing that I can do is pretty much what I do. Now to some people, that’s terribly restrictive I guess, but to me it doesn’t, oh God I’ve only scratched the surface.”

Harold Budd continues scratching the surface, one thoughtful waterdrop of a note at a time. He was #18 of 25 Icons of Echoes.

~John Diliberto