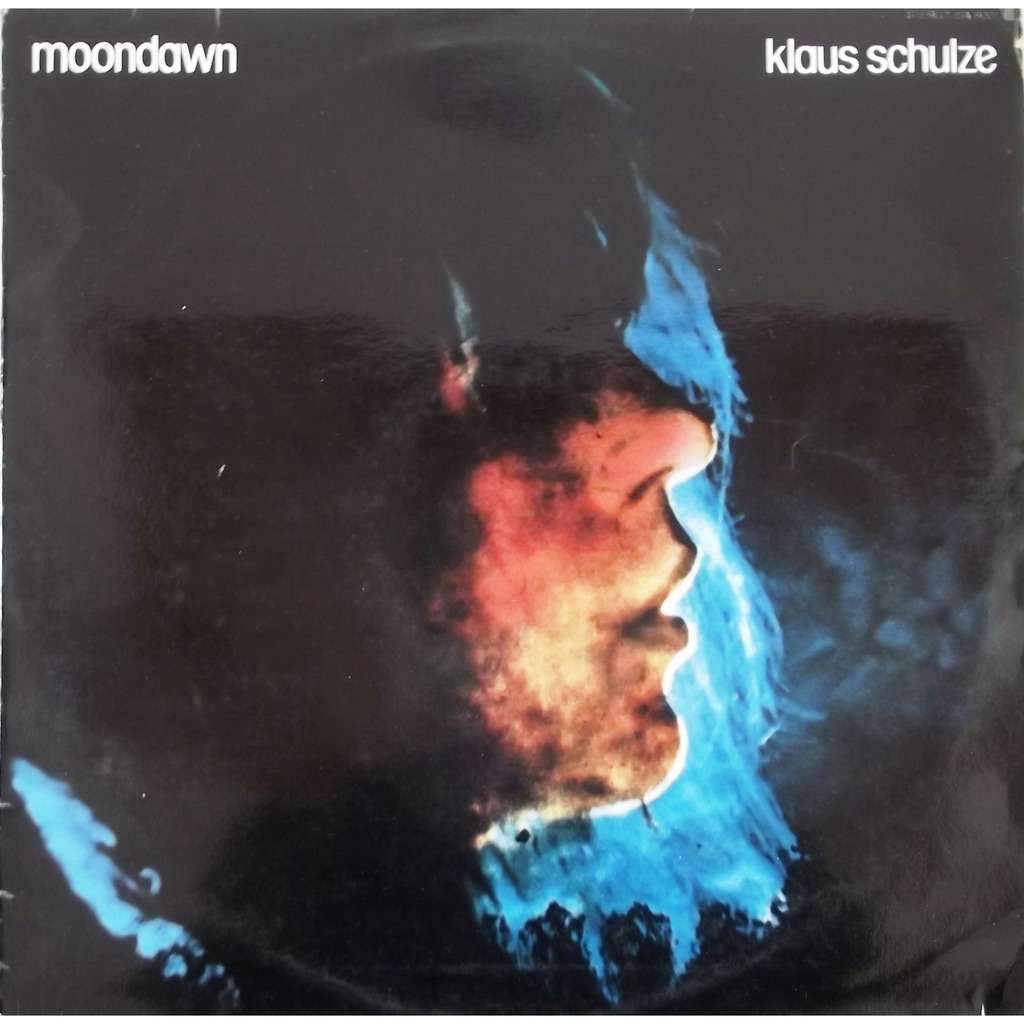

I wrote an a piece on Klaus Schulze several years ago. On the 40th anniversary of his Moondawn album, I update it a bit here.

Klaus Schulze’s Moondawn Turns 40

I It may not have sounded like it much in the last 15 or so years, but Klaus Schulze was part of the original genesis of Echoes. The albums he recorded in the 1970s and early 80s reside at the core of my music experiences. Albums like Moondawn, Timewind, X, and many more provided the soundtrack for many an imaginary movie during those years. The pulsing sequencers, free-form, note bending Moog solos, and spiraling, Escher-like architecture spoke of a world outside of conventional rock or classical musi, and a world outside of normal existence. Synthesist Mark Shreeve of Redshift once described Mirage as if it had “formed out of thin air, untouched by human hands.” Klaus’s music had that transcendental power, as if it came from somewhere beyond this mortal plane.

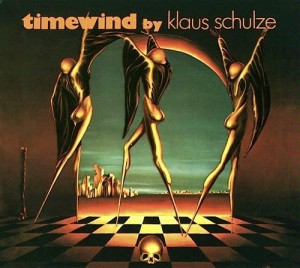

It may not have sounded like it much in the last 15 or so years, but Klaus Schulze was part of the original genesis of Echoes. The albums he recorded in the 1970s and early 80s reside at the core of my music experiences. Albums like Moondawn, Timewind, X, and many more provided the soundtrack for many an imaginary movie during those years. The pulsing sequencers, free-form, note bending Moog solos, and spiraling, Escher-like architecture spoke of a world outside of conventional rock or classical musi, and a world outside of normal existence. Synthesist Mark Shreeve of Redshift once described Mirage as if it had “formed out of thin air, untouched by human hands.” Klaus’s music had that transcendental power, as if it came from somewhere beyond this mortal plane.

Of course, Klaus was very much human, a garrulous guy with a corny sense of humor full of bad puns and capable of making human mistakes. In the 1980s, as psychedelics gave way to cocaine, Klaus became addicted and it affected his music badly. He admitted that alcohol and drugs made his music heavier and more turgid. “You drink and drink all day on the road and then after the concert there’s a party and you drink and drink and when I came back I realized that I couldn’t be without it,” he admitted in a 1988 interview for Totally Wired. “The music became heavier. Heavy Metal music must be for people who are alcoholics, because if you’re drunk and you listen to heavy metal it’s really nice. So i started to do heavy drum things and with Rainier and we were jumping around on stage.”

Of course, Klaus was very much human, a garrulous guy with a corny sense of humor full of bad puns and capable of making human mistakes. In the 1980s, as psychedelics gave way to cocaine, Klaus became addicted and it affected his music badly. He admitted that alcohol and drugs made his music heavier and more turgid. “You drink and drink all day on the road and then after the concert there’s a party and you drink and drink and when I came back I realized that I couldn’t be without it,” he admitted in a 1988 interview for Totally Wired. “The music became heavier. Heavy Metal music must be for people who are alcoholics, because if you’re drunk and you listen to heavy metal it’s really nice. So i started to do heavy drum things and with Rainier and we were jumping around on stage.”

Many of us began drifting away even as Schulze began churning out more and more music. There was the archival 10 CD Silver Edition in 1993, followed by the 10 CD Historic Edition in 1995 and the 25-disc box, Jubilee Edition. Schulze seemed intent on releasing every squiggle, bleep and fart he’d ever committed to tape. To his credit, he also continued to explore with form and technology, heading into experimental directions while his contemporaries desperately tried to sell out. As far back as 1983 he told me, “Sequencers! I just can’t hear them anymore.” But many of those experiments failed to spark the same interest as his early, groundbreaking works. Many of us became inured to his music and subsequent box sets and albums have gone unnoted by many formerly stalwart fans. That’s why you haven’t heard Klaus as much on Echoes as you have his acolytes like Steve Roach, Mark Shreeve, Robert Rich and Ian Boddy. That, and the fact that he still insists on creating opuses of 20, 30 and more minutes that just don’t work on the radio and are kind of unfair to the six other artists we could play in that period of time. (Are you listening Steve Roach?) But it should be said that neither Schulze or Roach are composing music with radio airplay in mind.

Over the last decade I’ve found myself returning to Klaus Schulze like a parishioner who has left the flock. Most all of his catalog has been re-released – much of it for the first time ever in the U.S. – in deluxe, nicely packaged editions. Despite failing to remaster the material for contemporary audio standards, Klaus’s music still holds up and the mystery and spectacle of Moondawn, Picture Music and Audentity still remains. Even recent materiel like Moonlake and Kontinuum recall the old glory, while not sounding as if they were stuck in 1976. This Friday,April 15, we’ll be featuring Klaus’ 6th album, Moondawn, released on April 16, 1976.

Moondawn is a seminal album. You can hear the transition from his earlier, more drone based work to sequencers right on this record. Each side of the album was a single composition. “Mindphaser” followed on his work on Blackdance and Picture Music with long, sustained chords on the Farfisa and Crumar keyboards, with fleeting solo lines drifting in like wraiths until about halfway through when Harald Grosskopf kicked in with the drums, playing free-form grooves while Schulze created elec tronic spirals on the Moog.

tronic spirals on the Moog.

It was “Floating” that was the kicker. After an alap-like opening of sample and hold bubbles and elongated pads, the sequencer groove kicks in, a simple two note pattern deployed through delays. With Grosskopf’s surging drums the track is a 27 minute excursion that accelerates into deep space. This was music that moved. I don’t know how many times I’ve listened to it riding trains while landscapes streamed by in apparent synchronicity with the music.

I still remember the first time I played this “Floating” on the Diaspar show on WXPN in Philadelphia in 1976. The phones lit up for the entire half hour. I called Jerry Gordon at 3rd Street Jazz & Rock, the best import store in Philadelphia, and said, “You better get a lot of copies of this.”

Tonight, we’ll play all of Klaus Schulze “Floating” in a Slow Flow Echoes.

IFIVE ESSENTIAL KLAUS SCHULZE CDs

Timewind,

Body Love

Mirage

X

Trancefer

(((( John Diliberto ))))

Nice article John!!