Peering Through the Drone of Big Ears 2016

Drones. Iconic alt-rock group out of depth. Charming elders of the old vanguard. A master of pink noise and symphonic expanse. More drones. Celtic Airs. Gothic metal.

Only at the 2016 Big Ears Festival..

The Big Ears Festival is a different kind of festival, one marked by civility more than partying. One where attendees are true music devotees, open to the most oblique musical constructs, the most elusive tangents, and the most extreme journeys into sound. Produced by Ashley Capps who also produces Bonnaroo, this annual event in Knoxville, Tennessee is a roadmap of new music past, present and future.

The Big Ears Festival is a different kind of festival, one marked by civility more than partying. One where attendees are true music devotees, open to the most oblique musical constructs, the most elusive tangents, and the most extreme journeys into sound. Produced by Ashley Capps who also produces Bonnaroo, this annual event in Knoxville, Tennessee is a roadmap of new music past, present and future.

Because Big Ears has become an annual pilgrimage to a sonic mecca, the decommissioned First Christian Church, now known as The Sanctuary, was the perfect place to start the 2016 festival. It was the site of Composer-in-Residence John Luther Adams’ installation, “Veils & Vespers.” The six hour long composition is an immersive work consisting of big slabs of droning sound coming out of multiple speakers mounted in The Sanctuary. The more you listened, the more layers were revealed: from sub-bass rumbles to mid-range swirls, and tiny high end interior movements, like insects scratching their way out of a shell. All those impressions are highly subjective, since many of the sounds are generated by overtones that hit everyone’s ear in different ways, depending on where you are in the room, and how your head is turned. Sometimes minimalist cycles, like very early Philip Glass, seemed to emerge. After about 45 minutes I swore I heard horns come in for a few seconds, followed by voices that sounded like a celestial choir. But it was all just pink noise, meticulously orchestrated by various algorithms by Adams.

“Veils & Vespers” established one of what I feel were the two dominant strains of Big Ears: drones. The other one was improvisation. But let’s stay with Adams for a few more moments, because in the evening, the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Steven Schick, unleashed all 42 minutes of Adams’ Pulitzer and Grammy Award-winning composition, “Become Ocean.” It’s an epic work that, like its name, flows and swells, sometimes in swirls and eddies, sometimes in wave-crashing crescendos. But like an ocean, instead of leading into a new movement, those waves literally just dissolved back into the ocean of symphonic sound. It was a work with the depth of its poetic source.

That evening’s program also included “Lachrimae”, a vanilla orchestral work by guitarist Bryce Dessner from the rock group The National, and Philip Glass’ kinetic “Cello Concerto No 2 ‘Naqoqatsi’” from his score to the Godfrey Reggio film. Cellist Maya Beiser took the role that Yo-Yo Ma played on the original recording. With its precise repetitions, Glass’ music is unforgiving of mistakes. Errant intonation and dropped notes can leave a performer naked. In this instance, the usually brilliant Beiser was stripped bare. It was all the more surprising given the flawless solo performance she presented the next day, playing works by Steve Reich, David Lang/Lou Reed, Golijov and her rocking version of Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir”.

But getting back to drones. And improvisation. And Yo La Tengo. The idiosyncratic alt-rock band came to the festival on the heels of their wonderful album, Stuff Like That There, which is full of ruminative songs and moods. But when they mounted the stage of the brand new venue, The Mill & Mine, they told the audience that since most people here had heard their music before, they were going to give us something different. Joined by Bryce Dessner on guitar, reed player Danny Thompson from the Sun Ra Arkestra, electric harpist Mary Lattimore and keyboardist with The Necks, Chris Abrahams, they launched into a 50 minute or so freeform, drone-zone improvisation of feedback guitar, random horn interjections and space age harp that was numbing in its total lack of cohesion or intent. I stuck with it to the bitter end, hoping that it might actually congeal into something coherent, or they might even, you know, play a song. They didn’t. The exercise in self-indulgence continued until the encore, where the trio sang a tune. But it was too little, too late, and not so great.

They could have learned a lesson from The Necks, the Australian free jazz trio, who are noted for their lengthy free improvisations that can run for an hour or so. Despite starting from zero, The Necks always arrive at points of consensus and the journey to those intersections is always a compelling display of intuitive interplay.

Further delights in improvisation were found with the Anthony Braxton 10+1tet. It was a typically knotty and convoluted Braxton composition, but was brought to life by the tight ensemble interplay and controlled improvisations. Braxton’s music doesn’t always provide touchstones, but this one had them, with walking basslines, contrapuntal rounds and Gershwin-meets-Picasso arrangements. Braxton himself created a flurry of overblown notes on soprano and alto saxophones. How cerebral is Braxton? In the midst of this joyfully tumultuous excursion, he was writing down notes, possibly rearranging his work on the fly.

There were several duets that also drew lines in the improvisational sand. Zeena Parkins played a self-designed, miniature harp, more like a zither, that is wired with electronic sensors on the crossbar, soundboard and column. Parkins’ harp is rarely plucked, and you’ll be hard put to find a glissando, but she would tap, strum and rub the strings with a wash brush. Joined by Tony Buck, drummer from The Necks, they stormed through a set that didn’t have much form and structure, but seemed to exult in the joy of noise. Parkins had a slightly maniacal smile while she played.

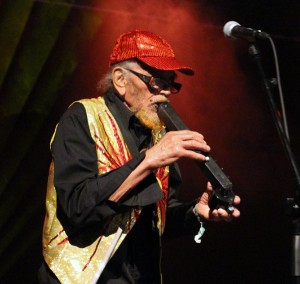

Another duo found Sun Ra Arkestra leader Marshall Allen teaming up with Chicago house musician, Hieroglyphic Being. They also played a non-stop hour long set. Hieroglyphic Being, aka Jamal Moss, chose a fairly serene and rhythmic electronic palette for Allen to solo over on alto saxophone and electronic wind instrument. The wizened 92-year-old musician only gained strength and intensity as the set progressed, with

him pummeling the keys of his sax. His EWI playing was full of bleeps, bloops and electronic slides that seemed to echo his former bandleader, Sun Ra. Playing his handheld Casio VL-Tone keyboard, he walked to the front of the stage glaring, playfully, at the audience.

On Saturday morning, it was Drones at 12 o’clock high. You felt like a flying fortress traversing a flak attack – it seemed like there were drones everywhere. Actually, it was 12 noon when Lou Reed’s “Drones” took flight. It’s an installation work that had six electric guitars leaning face-in against six amplifiers turned to 11, with another guitar face-up on the floor. While the guitars fed-back across a range of frequencies, Stuart Hurwood, the late Lou Reed’s guitar tech, moved among the semi-circle array, tweaking treble, bass, reverb and tremolo controls on the amps. It generated a similar effect to Reed’s notorious Metal Machine Music, but was easier to take, creating an immersive environment of shifting textures.

Lou Reed’s influence, along with LaMonte Young’s, could be felt in the hour-long presentation of Tony Conrad’s Outside the Dream Syndicate, originally recorded with the German avant-rock band, Faust in 1973. This live performance was exhilarating, in a trance sort of way. Zappi Diermaier, the original drummer of Faust, planted his massive frame behind a pair of tom-toms, a cymbal and a hi-hat and proceeded to pound out the one-beat groove of the work. Meanwhile, fellow Faustian, bassist Jean-Hervé Péron, played bass notes on the beat, carving out a dronescape along with a violinist and two string bass players, who sawed away on their instruments in this sonic assault.

Surprisingly, Laurie Anderson joined the band, but few saw her. Dressed in black, unlit, she stood behind an amplifier stack unseen, her eyes closed, bowing her electric violin gently. About 15 minutes in, she faded into darkness and disappeared.

Laurie Anderson was front and center in her evening with Philip Glass. The two veterans of New York’s downtown scene from the 1970s alternated playing each other’s songs. Anderson only had one of her narrative works, concentrating instead on her beautiful-sounding electric violin, which she has developed with lush harmonization effects. The highlight was two spoken word pieces. One featured the late Allen Ginsberg passionately extolling “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” his hymn to the middle-American wasteland. That was followed shortly by a spoken/sung work by Laurie Anderson’s late husband, Lou Reed. It was a poignant reading that had the feel of a gospel hymn. Glass and Anderson played a charming set, but it lacked the epic power of their solo works, which can leave you breathless.

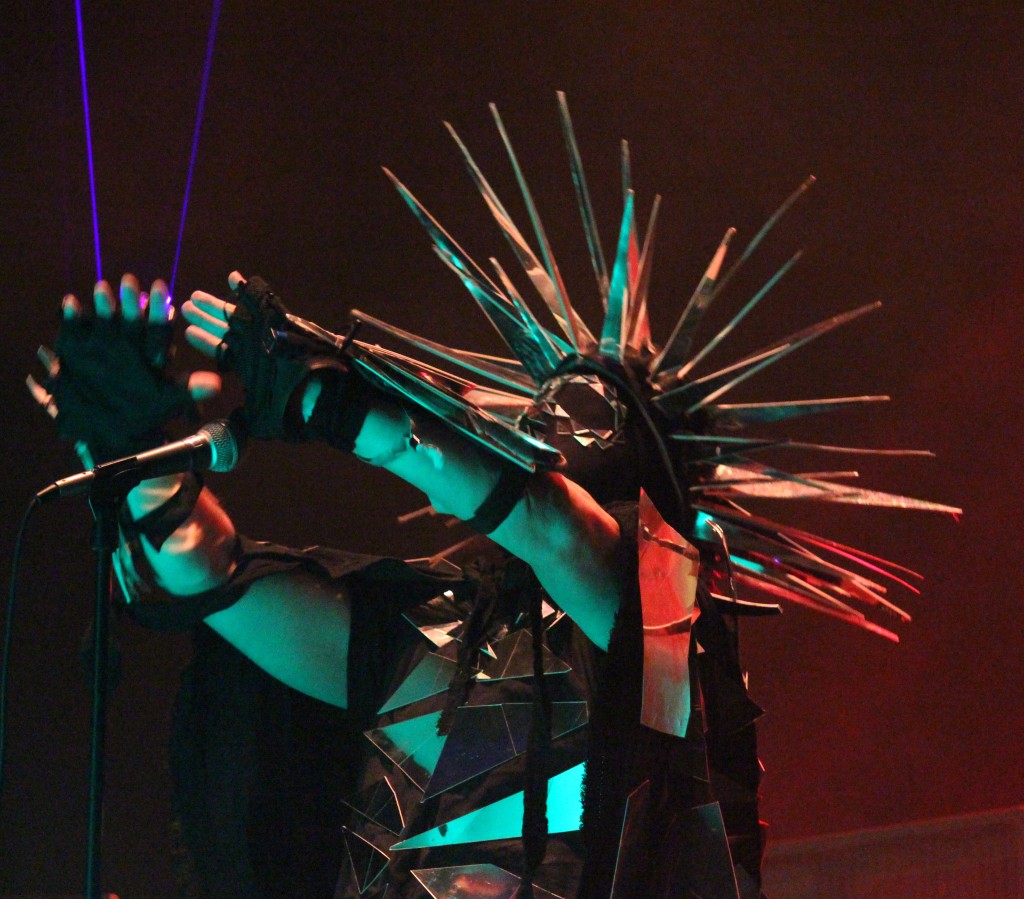

And did I mention drones? Sunn O))) delivered the loudest set of the festival. No drummer, no rhythm and no melody, just two guitarists and two electronic musicians sitting in front of a massive set of 11 amplifier stacks, grinding out a set that took Lou Reed’s Drones into even more pummeling dimensions. Compared to most of Big Ears, it was a heavily-staged performance mounted in the largest venue, The Tennessee Theatre. The musicians were all dressed in druid robes with hoods that hid their faces and stalked the stage amidst flash pots that tossed up bolts of fire and smoke. It was an unrelenting attack, like having your head stuck in a jet engine, but the textures were rich in overtones and texture. Singer Attila Csihar (Mayhem) came out with scorched earth exhortations that were impossible to discern, although I think I picked out the word “evil” a few times. His face was masked to look distorted and melted. For their finale, he shed his druid robes in favor of one made of broken mirrors, a mirrored mask and a halo of long spikes. Sunn O))) make most heavy metal acts sound like a kumbaya circle. That said, although they challenged last year’s performance by The Swans for pure volume, I could still hear after Sunn O)))’s sonic assault.

Sunn O))) started nearly an hour late and I lost patience just before they went on, so I decided to head across the street to the Bijou, where Angel Olsen played. returning to the Tennessee Theater later to be bludgeoned by Sunn O))). Even though she’s played the festival in the past, I’m still not sure what Olsen was doing at Big Ears. Her brand of country-fringed alt-rock seemed out of place at the festival, or at least the path I took through it. But she was a welcome and charming respite from the drones and meandering improvisations.

Likewise, The Gloaming offered a stark contrast to most of the festival’s offerings. A Celtic group consisting of ex-Afro Celts singer Iarla O’Lionaird, fiddler Martin Hayes, guitarist Dennis Cahill, hardanger fiddler Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh, and pianist Thomas Bartlett, aka Doveman. They expand the breadth of Celtic music while not moving too far off it. They spun-out reels with minimalist perfection, while O’Lionaird found a home for his soulful sean-nós vocals. It was Bartlett who set the group apart. He deployed spare, but melodically rich counterpoints to the Celtic dance, sounding more like Keith Jarrett in a contemplative mood or Arvo Pärt in a frisky one.

Even his overly histrionic, stage presence, swaying, waving his hands, dressed in a bathrobe with a bottle and glass of wine at hand, couldn’t detract from his delicately-placed accents. These are master musicians, playing an impressionistic and introspective brand of Celtic music.

The official festival ended with a 1 AM set of the electronic ambient dance sounds of Kiasmos, with Ólafur Arnalds and Janus Rasmussen bopping and dancing behind computers and controllers, unfolding remixes of their electronic chamber dance sound.

There was one more event on Sunday, John Luther Adams’ outdoor percussion piece, “Inuksuit” staged across the expanse of Ijams Nature Center. It looked like an impressive and fun work, but since it was scheduled late, I’d already booked a flight out before it was announced.

This was my second year in a row at Big Ears, and while I left last year exhilarated, I found myself exhausted and somewhat thrashed this year, like I’d been in a washing machine hybridized with an MRI. Perhaps the route I took through the festival tilted my perception. It’s impossible to catch everything and scheduling conflicts forced me to miss the Sun Ra Arkestra, who I’ve seen many times before, Andrew Bird, and many others. While John Luther Adams’ “Become Ocean”, The Gloaming and Anthony Braxton scaled the heights, for many other shows I felt cerebrally engaged, but emotionally and viscerally distant. Nevertheless, it was another thrilling and challenging Big Ears.

~John Diliberto