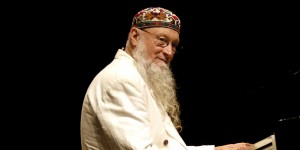

Terry Riley Turns 80!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Hear this interview in the Echoes Podcast here or download it from iTunes.

What do musicians such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass have in common? How about Brian Eno or German electronic bands like Tangerine Dream? What links rock acts like The Velvet Underground and The Who? And for that matter, what links them all to New Age artists like Kitaro? They all share the inspiration of composer, Terry Riley who turns 80 years old on June 24. He’s influenced each of these musical artists and a lot of the music you currently hear on Echoes. As he hits 80, he is as active as he’s ever been, composing compositions for the Kronos Quartet. A new collection of their music together has just been released, Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector. I’ve interviewed Terry a few times in the 1980s and early 1990s, all at his Shri Moonshine Ranch in Northern California.

What do musicians such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass have in common? How about Brian Eno or German electronic bands like Tangerine Dream? What links rock acts like The Velvet Underground and The Who? And for that matter, what links them all to New Age artists like Kitaro? They all share the inspiration of composer, Terry Riley who turns 80 years old on June 24. He’s influenced each of these musical artists and a lot of the music you currently hear on Echoes. As he hits 80, he is as active as he’s ever been, composing compositions for the Kronos Quartet. A new collection of their music together has just been released, Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector. I’ve interviewed Terry a few times in the 1980s and early 1990s, all at his Shri Moonshine Ranch in Northern California.

Terry Riley lives tucked away in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Northern California on his Shri Moonshine Ranch. That is where he opens the gate with cowbells on it to a vast field. The sound of his dog’s bark echoing off the mountains near his home in 1988 serves as a metaphor for Riley’s own music which has used echo, delays and looping. Yet, his career has done anything but loop. His music was birthed minimalism, charted a new course in just intonation and launched a second career as a classical composer. It all goes back to a piece he composed in 1964 called “In C.” To some contemporary ears, it might sound a bit cacophonous, but in 1968, when it was recorded, it sounded different.

“At the time I did it, I thought it was clearing things up because it seemed like music was in a real cacophonous period,” explained Riley. “You know, the early ‘60s, especially contemporary music. So ‘In C’ seemed like kind of a clear little gem, like something, you know, sparkling and bright. But I guess looking at, looking at it in the light of the more mellow New Age music, it would seem that way.”

“In C” was the ignition switch of minimalism. Even La Monte Young, the Godfather of minimalism, acknowledges Riley’s influence on the style.

“And you know Steve Reich played “In C” in California before it’s New York presentation and he used to hang out around Terry Riley and he heard Riley’s work early,” conceded Young, back in the 1980s. “Steve himself has admitted this kind of influence through Riley on him. Although I don’t think Phil Glass acknowledges any influences it’s well known that Steve and Phil had a group together.”

It all began in Paris where Terry Riley played piano on military bases. He was classically trained, jazz toned and hallucinogenically inclined. He started working with tape loops, which in the early 60s, was a new concept.

It all began in Paris where Terry Riley played piano on military bases. He was classically trained, jazz toned and hallucinogenically inclined. He started working with tape loops, which in the early 60s, was a new concept.

“They had primitive tape recorder, Wollensaks, you know, these old tape recorders that you could get in the ‘50s,” recalled Riley. “And we worked with those in making loops. And so that’s how I got started. Loops were the first opportunity to hear something over and over again like that.”

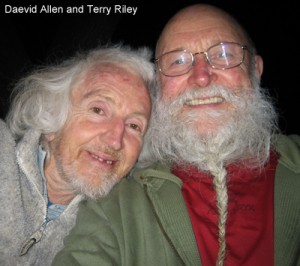

Daevid Allen, the late founder of the progressive rock groups, the Soft Machine and Gong, explored the world of loops with Riley.

“Yeah we are very very good friends and we met very early on,” Allen fondly recalled backstage at Nearfest in 2009. “We were both selling Herald Tribunes on the backs of motor scooters in Paris. And that was the time when he was composing ‘Mescaline Mix‘ and was working with a very adventurous dance company, during happenings and events in Paris in the early 60s.”

Allen and Riley would reputedly make tapes loops that circles the room and went out windows. “He taught me how to make tape loops, which is huge for me because that was a very important thing for me to understand the nature of, repetitive music,” said Allen. “And the trance value of it. And how when you did it live, it had yet another value and quality to it. He has always been a teacher. I have always looked up to him spiritually and musically as my guru.”

Riley compositions like “Mescaline Mix” and “Music for the Gift” used found sounds or looping orchestrations of recordings as their source materiel. It was his 1964 composition, “In C” that codified his early concepts. The piece consists of 53 short sequenced musical phrases where each phrase is played in order by any number of musicians. However, each phrase can be played as long as the musician performing it desires.

“In C,” which was my first written piece for instruments, definitely has the same feeling and does the same thing,” explained Riley. “I got a lot of feedback from my electronic work, which enabled me to conceptualize “In C.” But you can play it without the technology.”

In fact, you can play it on just about anything. There have been versions for piano orchestras, guitar orchestras, and African Ensembles. Trumpeter Jon Hassell played on the first recording of “In C” and worked with both Riley and La Monte Young. Hassell also helped mix a rendition of “In C” with the Shanghai Film Orchestra.

In fact, you can play it on just about anything. There have been versions for piano orchestras, guitar orchestras, and African Ensembles. Trumpeter Jon Hassell played on the first recording of “In C” and worked with both Riley and La Monte Young. Hassell also helped mix a rendition of “In C” with the Shanghai Film Orchestra.

“It’s like a process piece in a way where, like all good ideas, they can change as the time changes and as was exemplified by this Chinese orchestra,” noted Jon Hassell. “I mean he had pipa, Chinese lutes and all sorts of strange Chinese instruments playing these patterns and it sort of breathed new life into it. So, you know it still stands as a kind of a touchstone for that whole epoch.”

“In C” led to “A Rainbow In Curved Air” and “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band,” compositions based on Terry Riley’s looping performances on electric organ and soprano saxophone. These compositions sent a generation into mind-expanding dreams and sequencer cycles.

“I think I was probably the first person to start using a delay in live performance,” claimed Riley. “I know I was the first person to use the long-term delay between two tape recorders, like you get in “Poppy Nogood.” And then the when I was doing “Rainbow,” I always had the desire to have this short term delay, so I was for a long time I did it with a tape recorder.”

“I think that echo and all these devices which change the ambience of music are drug-like in the sense that they pull the, they pull the listener in deeper than he would get otherwise,” observed Riley, noting that “A Rainbow In Curved Air” plugged into the psychedelic spirit of the times. “They kind of create this softness that you can go into. It goes back to if you’ve ever sung in a cave or gotten in the Taj Mahal and whooped and hollered. I mean those experiences are very deep and moving. So I feel, it creates a stasis of the sound, a tape loop in that you can watch something as if it were stopped in a camera frame. And it’s repeating over and over again and you start to notice the real, the real deep details that draws the mind in also.”

Riley’s A Rainbow In Curved Air laid the groundwork for German space music bands like Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze, as well as Brian Eno’s ambient music. Robert Rich is a second-generation disciple of this sound.

Riley’s A Rainbow In Curved Air laid the groundwork for German space music bands like Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze, as well as Brian Eno’s ambient music. Robert Rich is a second-generation disciple of this sound.

“Terry Riley especially influenced them, you know, when he would tour with his tape loops back in the late ‘60s on Rainbow and Curved Air in 1968,” he observes.

“Absolutely transformative! Those people heard that and wanted to do that, but they didn’t have the chops that Terry had, so they used the Moog sequencer.”

Riley’s music reached popular consciousness via The Who’s “Baba O’Riley,” named after him and using his cyclical techniques and Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells.

“Terry Riley…” said Mike Oldfield, drifting back a couple of decades to his teen years. “I remember when A Rainbow in Curved Air was a popular album around in that time and he had this ostinato thing going on. Yeah, I used to listen to that and in a way that influenced me with the beginning of Tubular Bells. It’s quite a simple trick. You know you hear it a lot in film scores these days, especially on piano: repetitious ostinato phrase with a hammering on the thumb.”

Underscoring all of Riley’s work are his Eastern studies in religion, philosophy and music. He, along with La Monte Young, studied extensively with Indian singer Pandit Pranath.

“I’d been interested in India as a spiritual center for years and years,” proclaimed Riley. “When I met Pandit Pranath and was able to go to India with him, I was introduced to some very high yogis who were his spirit teachers, and had a chance firsthand to see some of the things I’d seen in books or experienced in people, the kinds of people I’d been reading about. And he has taught us that music practice is as fine a way to practice religion as any. Through music you can become one with God.”

In the 1980s, Riley began moving further away from his minimalist roots. He recorded a double LP of a solo piano work called The Harp of New Albion. Played on a piano tuned in just intonation, it was by turns expansive, rhapsodic, poetic and stormy.

Well I feel with playing that piece, pretty free.” He explained. “I feel like I can go in almost any direction I want to go, that’s possible within the tuning, that is, and with the piano. Also, the piano I feel gives me a lot more liberty than I’d experienced before with electronic instruments in the sense of the way I can phrase or even orchestrate.

The biggest change in Riley’s career has been his association with the Kronos Quartet. The adventurous new music string ensemble has been commissioning works from the composer non-stop for 35 years. When Riley began composing for Kronos in 1980, he’d never written a string quartet before and hadn’t really written music for other ensembles. Former Kronos Cellist Joan Jeanrenaud remembers their first encounter.

“It was really nice when we first worked with him because we went up to his ranch,” she recalled fondly in her gentle Tennessee drawl. “It was a very slow process. He had these little things written on scraps of paper and we sort of put them together in some order. He also sang with us and played his keyboard and sang. He couldn’t have written anything down at first without going through that process with somebody. It actually was very revealing too and from that we learned a lot about Terry’s music than if we had just been presented with a finished score.”

“Well, he would be the first to say that his pieces for Kronos are, in his own mind, the most important works he’s notated,” maintained David Harrington, founding member and violinist with Kronos. “I always have this sense that when he’s doing something new for us, he’s mindful of what he’s done before but he’s, like, pushing himself. Like, he doesn’t want to write another “Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector” or another “Cadenza on the Night Plain,” or “Salome Dances for Peace,” or “The Cusp of Magic.” He wants to kind of bring Kronos into the area where he’s at, right at that moment.”

The results have been dozens of compositions of Terry Riley’s that Kronos has performed and recorded. Listening to the music Terry Riley has been recording with the Kronos Quartet over the last 35 years, you might not recognize him as a minimalist composer at all.

The results have been dozens of compositions of Terry Riley’s that Kronos has performed and recorded. Listening to the music Terry Riley has been recording with the Kronos Quartet over the last 35 years, you might not recognize him as a minimalist composer at all.

“Yeah, that’s probably, that’s probably true of me,” agrees Riley, But it’s true of probably most of the composers that have been associated with minimalism. Now, they’re all saying they don’t like the restrictions of being considered [minimalist], but this is something you get stuck with no matter what you do, you know. If you become a heavyweight champion of the world and later you become a great chef, you’re always going to be known as the heavyweight champion of the world.”

Yet whether composing for string quartet, Chinese pipa or solo keyboard, Terry Riley has become a musical world unto himself. He has outlived his own influence from 50 years ago, to become a vital composer deep into the 21st century.

“For me it’s a goal for myself to try to take the music into the highest and purest level I can, that is working itself out the truest level,” asserted Riley.

Terry Riley turned 80 on June 24. He is currently working on new music with the Kronos Quartet as well as performing solo and with his son, Gyan Riley and violinist Tracy Silverman. He’s just released a collection of his work with Kronos called Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector.

~John Diliberto

More on Terry Riley

Thoughts in Sound

Wu Man in Echoes Podcast

John you have put together a wonderful portrait here. It was so good to hear all the voices and thoughts of other musicians