There was never any doubt of Charlie Haden’s commitment to the bass and to jazz. From the iconoclastic Ornette Coleman Quartet in the late 50s to his Quartet West ensemble, Haden has remained a steadfast force in jazz, constantly changing, but always remaining true to himself and his art. Charlie Haden died, on July 11, 2014, just shy of his 77th birthday.

There was never any doubt of Charlie Haden’s commitment to the bass and to jazz. From the iconoclastic Ornette Coleman Quartet in the late 50s to his Quartet West ensemble, Haden has remained a steadfast force in jazz, constantly changing, but always remaining true to himself and his art. Charlie Haden died, on July 11, 2014, just shy of his 77th birthday.

In a 1996 Jazz Profile program for National Public Radio, Charlie Haden said, “We’re here to bring beauty to the world, and make a difference in this planet, to enhance people’s lives, to improve the quality of life with depth and beauty. That’s what art forms are about. And it takes your life, you know. If you are a painter, you have to give for every stroke; if you are a musician, for every note.”

Charlie Haden did that and more. Born in Shenandoah, Iowa in 1937 he was thrust into music instantly. His parents were both country singers appearing on the Grand Ole Opry and growing up, visitors to the Haden home included Mother Maybelle Carter and the Carter Family. “My dad and mother were both on the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville before I was born, and my mom and dad had a radio show, as the Haden Family around 1933, ’34,”recalled Haden. “This was in Shenandoah, Iowa, at a radio station with the call letters KMA, 50,000 watts. I started singing on the show when I was 22 months old.”

He was Cowboy Charlie and recordings of his singing on the show still exist. His career was sidetracked by polio which made it difficult to sing so he started playing bass. Hearing Charlie Parker and Lester Young in 1952 set his direction. “I went to a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert at Central High Auditorium where they performed and it was unbelievable,” he exuded, in the quiet, understated way that Haden showed enthusiasm. “It was so exciting to hear this music and these musicians and their dedication to the music. It was what I wanted to do from then on, just to play.

Moving to LA thrust him into the heart of the jazz scene there. He began playing with alto saxophonist Art Pepper, tenor legend, Dexter Gordon, and a pianist named Paul Bley. In 1956 Bley led a band at the Hillcrest Club that included vibraphonist Dave Pike, drummer Lennie McBrowne and a young Charlie Haden.

“He didn’t know one note from the other,” related Bley in his sardonic fashion. “But he had great time and I figured it was better to have somebody who could learn the right notes rather than have somebody who had the right notes and didn’t have time.” Haden apparently improved enough to make his recording debut on Paul Bley’s Solemn Meditation, in 1957.

A meeting with alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman locked in what became Charlie Haden’s reputation for life when Ornette invited him to jam. “I was so scared man,” laughed Haden, “but we started to play, and the whole world lit up for me. All of a sudden, I had permission to do what I’d been hearing all this time, and this guy was taking me on a journey, and it allowed me to really learn about the art of listening, because it’s so important to listen when you’re playing, and in order to play with Ornette, I had to listen to every note that he played, because he was constantly modulating from one key to another.” Haden went on to record several iconic recordings with Ornette including The Shape of Jazz to Come. Coleman’s music remained part of Haden’s repertoire, including the explosive 1980s band Old & New Dreams, essentially the Ornette Coleman Quintet without Ornette.

A meeting with alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman locked in what became Charlie Haden’s reputation for life when Ornette invited him to jam. “I was so scared man,” laughed Haden, “but we started to play, and the whole world lit up for me. All of a sudden, I had permission to do what I’d been hearing all this time, and this guy was taking me on a journey, and it allowed me to really learn about the art of listening, because it’s so important to listen when you’re playing, and in order to play with Ornette, I had to listen to every note that he played, because he was constantly modulating from one key to another.” Haden went on to record several iconic recordings with Ornette including The Shape of Jazz to Come. Coleman’s music remained part of Haden’s repertoire, including the explosive 1980s band Old & New Dreams, essentially the Ornette Coleman Quintet without Ornette.

Haden was always sought by musicians looking for more than a time keeper. They wanted a musician with an intuitive sense of melody and a psychic ability to follow every musical deviation, detour and unexpected turn. He served that roll with many musicians, but most notably, pianist Keith Jarrett in whose quartet he played from 1967 to 1979. “Charlie is an obsessive player in the sense that he is not interested blending only,” says Jarrett. “He doesn’t rely on someone else’s ideas of what music is. He has his own. I’m obsessive, he’s obsessive, Paul’s [Motian] obsessive. Those are the guys I want to pay with. At the point where you are about to go insane is the point where the music starts to happen.”

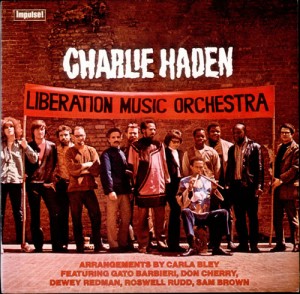

In a politically charged era, Charlie Haden was more political than most. He formed the Liberation Music Orchestra to protest the Vietnam War. He recorded three albums with the group, all arranged by Carla Bley who took Haden’s interpretations of Spanish Civil War folk songs and turned them into jazz. “I wasn’t involved with any politics,” laughed Carla Bley. “I thought JFK was great and when Charlie told me he wasn’t I was shocked, and then I was a little more careful about what I liked and didn’t like, I was a little more cautious. He was the total political guy of that whole bunch of us.”

In a politically charged era, Charlie Haden was more political than most. He formed the Liberation Music Orchestra to protest the Vietnam War. He recorded three albums with the group, all arranged by Carla Bley who took Haden’s interpretations of Spanish Civil War folk songs and turned them into jazz. “I wasn’t involved with any politics,” laughed Carla Bley. “I thought JFK was great and when Charlie told me he wasn’t I was shocked, and then I was a little more careful about what I liked and didn’t like, I was a little more cautious. He was the total political guy of that whole bunch of us.”

Haden said he was always political. “Since the first time I saw racism,” he said ruefully. “And the first time I saw hypocrisy in organized religion. I saw lots of poverty and I saw lots of racism, you know, I was politicized very early, because of where I was living. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to leave as soon as I could.”

Charlie Haden’s sound was deep and soulful, as if he’d taken the measure of the world in all its sadness and transposed it to his 4 strings. That’s what made him such a sensitive duet artist. Just listen to his album, The Golden Number, featuring pairings with trumpeter Don Cherry, saxophonist Archie Shepp, pianist Hampton Hawes and Ornette Coleman, playing trumpet instead of alto saxophone. Haden takes each of these musicians into rarefied space. His album with guitarist Pat Metheny, Beyond the Missouri Sky, is an understated masterpiece, tapping both of their folk roots.

For someone who was as deep into drugs as Haden, he maintained his boyish looks right up until the end. But heroin plagued him for much of his career. It’s why he left the Ornette Coleman band in the 60s and drugs created the slide out of the Keith Jarrett Quartet.

Jarrett had nothing but love for Charlie Haden and respect for his playing, but even that wasn’t enough. “Charlie was having a drug problem and Dewey [Redman] was having probably the same kind of thing, he ruefully recalls. “We were in Atlanta once playing in a club, and during this set I might look up and Dewey would be not really there, not entering the melody sections. I’d be waiting and I’d keep playing introductions and the introduction would become the piece. Then when we were all playing together I’d hear the bass drop out now and then and I’d look up and Charlie would be adjusting a bass cover to keep the sweat off, but missing some beats in the meantime. So I mean, as important as it is to keep the sweat of your bass, if you’re into the music you’re not thinking about that. I remember saying, “Look, I want you guys to leave the stage. I’m going to do this the rest of the night alone. So that was one of those experiences.”

Haden finally got clean for good and other than the ring of tinnitus, he remained relatively healthy in teh 90s and early 2000s, recording with his Quartet West, a retro jazz group that sounded like it could’ve sat in at Rick’s Café Américain. He revisited his own roots on Ramblin’ Boy, playing old American folk songs with an all-star cast of jazz, folk, country and rock musicians. It was a surprising change for this musician who had spent most of his career on the bleeding edge of free jazz and improvisation.But even late in his life he would still play with Ornette Coleman, now the last man standing of that original coterie of free jazzers that included Don Cherry, Ed Blackwell, Billy Higgins, and Dewey Redman. He also recorded with Keith Jarrett again including the recently released album, Last Dance, a sadly prophetic title.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8eMfc6TjoA

Charlie Haden was a musician who refused to be locked into a category. He recorded contemporary classical music with Gavin Bryars and blues with James Cotton. He appeared on records with Rickie Lee Jones and Bruce Hornsby. He even won Grammies for Latin jazz albums in 2001 and 2003, But at his core, Haden remained dedicated to jazz, no matter how trying that might be at times.

“If you’re really serious about your art form,” he reflected, “and you’re really dedicated to your art form, you have to be willing to give your life for your art form. I’ve always felt that.”

When I conducted interviews for my 1996 radio documentary on Charlie Haden for NPR’s Jazz Profiles, there wasn’t a single person I interviewed who had anything but love for this musician, an artist who embodied integrity, exploration and social consciousness. Now, Charlie Haden is gone at age 76. In the last several years, Post-Polio Syndrome kicked in and Haden’s health and speech degenerated, finally leading to his death on July 11. He’s survived by his wife, singer Ruth Cameron, and four children, the triplets Petra, Tanya and Rachel, and a son, Josh, all of them musicians.

John Diliberto (((echoes)))