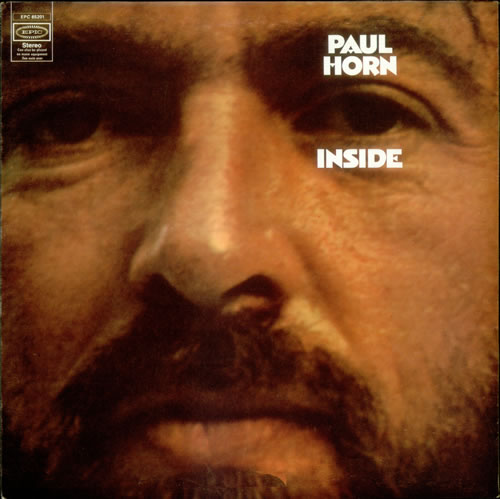

To understand the importance of Paul Horn you have to cast back to a time, 1969, when there was no New Age music. Few artists in the west were thinking about a contemplative musical sound. There were no important albums outside of classical music that were pure solo flute and certainly none that plied the echoing spaces heard on Paul Horn’s Inside, an album of solo flute improvisations made inside the Taj Mahal in India.The sounds that echoed in that ancient space had reverberations throughout music for years to come.

To understand the importance of Paul Horn you have to cast back to a time, 1969, when there was no New Age music. Few artists in the west were thinking about a contemplative musical sound. There were no important albums outside of classical music that were pure solo flute and certainly none that plied the echoing spaces heard on Paul Horn’s Inside, an album of solo flute improvisations made inside the Taj Mahal in India.The sounds that echoed in that ancient space had reverberations throughout music for years to come.

Now, at the age of 84, the influential flute and saxophone player Paul Horn has passed away. He left the planet on June 29 in Vancouver, British Columbia after an undisclosed illness.

You haven’t heard the name Paul Horn much in the new millennium but in the second half of the 20th century, his flute was everywhere. He played jazz with Chico Hamilton, recorded with Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole, played flute on countless pop songs and won a Grammy for best original jazz composition for his 1966 album, Jazz Suite on the Mass Texts.

But Paul Horn is best remembered as an early avatar of the New Age.

His 1968 album, Inside, recorded inside the Taj Mahal, is often cited as a precursor to this new music and he continued making recordings that moved him further from his jazz reputation in the ensuing years. So far, in fact, that he was given a Crystal Award, the new age version of a Grammy, in 1990 at what turned out to be the third and final Annual International New Age Music Conference in Los Angeles. The award coincided with Horn’s 20th anniversary recording, Inside the Taj Mahal II, and the publication of his autobiography Inside Paul Horn: The Spiritual Odyssey of a Universal Traveler.

His 1968 album, Inside, recorded inside the Taj Mahal, is often cited as a precursor to this new music and he continued making recordings that moved him further from his jazz reputation in the ensuing years. So far, in fact, that he was given a Crystal Award, the new age version of a Grammy, in 1990 at what turned out to be the third and final Annual International New Age Music Conference in Los Angeles. The award coincided with Horn’s 20th anniversary recording, Inside the Taj Mahal II, and the publication of his autobiography Inside Paul Horn: The Spiritual Odyssey of a Universal Traveler.

While many “legit” musicians ran away from the New Age brush, Paul Horn had no qualms being associated with the genre or its culture. He thought it was a different music with different criteria. “This music cannot be evaluated using the same standards of evaluating that people usually do. ‘Cause it’s not based on virtuosity,” explained the virtuoso in a 1990 interview. “The purpose of it is not necessarily just entertainment. It’s to take a person to a quieter state within themselves and in that quietness, they are going to experience, they are going to have another experience. And that to me is the beginning of a spiritual experience, ’cause all those things come from within yourself.”

While many “legit” musicians ran away from the New Age brush, Paul Horn had no qualms being associated with the genre or its culture. He thought it was a different music with different criteria. “This music cannot be evaluated using the same standards of evaluating that people usually do. ‘Cause it’s not based on virtuosity,” explained the virtuoso in a 1990 interview. “The purpose of it is not necessarily just entertainment. It’s to take a person to a quieter state within themselves and in that quietness, they are going to experience, they are going to have another experience. And that to me is the beginning of a spiritual experience, ’cause all those things come from within yourself.”

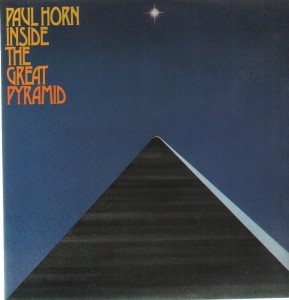

Unlike so many classical and jazz virtuosi, Paul Horn understood the pathway into that experience. Playing in the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramid gave him an understanding of silence. “Because if I play too many notes, without allowing enough space, then it gets to be all jumbled,” he observed “as anyone who has tried singing in a men’s locker room in a gymnasium or something or women’s locker room or gymnasium would know. You have to allow space for the echo to repeat what you’ve done and to go through whatever the overtones are and all the acoustics of the place. You give it a chance to participate in the composition as well as me.”

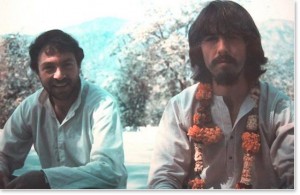

Classically trained, Paul Horn experienced the rigors of jazz, playing with Chico Hamilton, Duke Ellington and others. He released his solo debut album, House of Horn, in 1957 on Dot Records. But his embrace of a simpler music is entwined with his own spiritual path. He was a disciple of guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and had two extended stays at the guru’s ashram in the mid-1960s. The last time was the same sojourn that brought The Beatles, Mia Farrow, Donovan and some Beach Boys to the ashram. Horn actually became a teacher of transcendental meditation which he still practiced late into his life.

Classically trained, Paul Horn experienced the rigors of jazz, playing with Chico Hamilton, Duke Ellington and others. He released his solo debut album, House of Horn, in 1957 on Dot Records. But his embrace of a simpler music is entwined with his own spiritual path. He was a disciple of guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and had two extended stays at the guru’s ashram in the mid-1960s. The last time was the same sojourn that brought The Beatles, Mia Farrow, Donovan and some Beach Boys to the ashram. Horn actually became a teacher of transcendental meditation which he still practiced late into his life.

“Meditation is a technique to be still and when you’re still then there’s another experience that happened,” he explained. “But there’s great value in experiencing silence and being still and being awake not asleep, and then there’s another thing that happens and that thing adds another dimension to your life, which is very important.”

Another change in Horn’s orientation came when he toured with pop folk-singer Donovan in the late 60s. With Donovan, Horn discovered that communication might be more important than technique.

“Donovan is not a developed musician,” recalled Horn. “He’s not a Barney Kessel on guitar or Howard Roberts or Django Reinhart or any great guitar player. He plays simple chords and he has a nice, pleasing voice. I just saw that he got 25,000 people to be quiet. And he once made a comment to me, he said ‘My ultimate goal is to play a number and get the audience so quiet that they can’t even raise their hands to clap at the end. That would be my ultimate achievement as a performer’. And I thought that was pretty amazing to even come up with that concept.”

While Paul Horn was happy to be called a New Age musician, that doesn’t come close to capturing the depth and breadth of his art. He was never content to ride the solo flute in sacred spaces shtick. He went on to work with electronic instruments on Traveler and world music on Brazilian Images, Africa and his beautiful CD with David Mingyue Liang, China.His 1975 album, Paul Horn + Nexus is a forgotten gem with Horn improvising with the Nexus percussion ensemble. When you get down to it, Paul Horn’s life and music were just one beautiful extended improvisation, a raga of spiritual journey and musical exploration that should not be forgotten.

Paul Horn gone at age 84.

Five Essential Paul Horn CDs

Inside (1969, Epic)

Inside the Great Pyramid (1976)

Inside Canyon de Chelly (1997) – with R. Carlos Nakai

And one beautiful outlier that no one else will probably mention:

The Peace Album (1988) – gorgeous multi-tracked flute chorales for Christmas

John Diliberto (((echoes)))