She sang with Ornette Coleman, produced the first loft concerts of John Cage, La Monte Young and the Fluxus movement, created conceptual art, pre-saged Diamanda Galas and the B-52s. Then she married John Lennon.

“Count all the stars of that night by heart. The piece ends when all the orchestra members finish counting their stars or when it dawns. This can be done with windows instead of stars.” – Yoko Ono

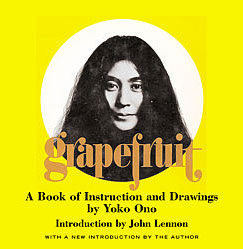

It sounds like something John Cage might’ve written in Silence or that Brian Eno would employ for an Oblique Strategies card. But it’s Yoko Ono’s “A Piece For Orchestra” from her 1964 book of humorous, Zen-like instructions, Grapefruit.

Context is everything. Yoko One was a conceptual artist in the 1960s. That means someone who’s work is meant to provoke, confront and instill a self-realization, like Cage’s “4’33”.” Ono wanted us to confront our assumptions and alter them. Look at this video from a 1965 performance of “Cut Piece.”

http://youtu.be/Zfe2qhI5Ix4

The assumptions about Yoko Ono run along the lines that she isn’t a serious artist, but rather a strange Asian woman who broke up The Beatles and went on to shriek on her own recordings. Even today, that’s the image for many, if not most people who know the name of Yoko Ono. Those assumptions should be challenged by anyone who has really listened to her music which I surveyed 20 years ago upon the release of Onobox, a six CD set from Rykodisc that drew from her vast catalogue of recordings from 1968 to 1985. With extensive liner notes from critic Robert Palmer, Onobox attempted to re-contextualize Ono. “We thought we had to change perceptions because the perception out there is that this is lousy music,” said project coordinator David Greenberg.

Yoko Ono was happy in her avant-garde world of the 1960s, organizing the first loft concerts for the Fluxus movement, a conclave of artists that included John Cage, LaMonte Young, Henry Flynt and Richard Maxfield. At the time, Ono was better known for her visual work and creating happenings or events, rather than music. Her name even came up last week in an interview with composer Joseph Byrd of the psychedelic rock group The United States of America who cited Ono as an early benefactor of his avant-garde work, producing concerts of his music in her loft.

Then she met John Lennon and it all changed. What had been a brave new voice of the avant-garde became a laughing stock of pop eccentricity. For Ono, it was a shock. “I was totally involved in what I was pursuing, which was new sounds, you know,” she said, recalling her own innocence as she emerged from the supportive world of Fluxus and into the Magical Mystery Tour. “I was totally excited about it. So when people are saying it’s self-indulgent or whatever, I didn’t understand what they meant.”

In March of 1992, Ono sat primly in her cavernous office in the Dakota building where she’s lived since 1973 and where John Lennon was shot to death. Painted clouds cover the ceiling and the decor runs from the elaborate Egyptian carvings on her desk and a Greek style divan to figurines from Asia and a porcelain Siamese cat with a light illuminating its eyes from the inside. As if a reminder of her early days, a Fluxus book sits conspicuously on the shelf behind her. With her diminutive frame and black hair, Yoko didn’t look like a woman who had seen six decades pass. The same could be said for eight decades at 80. Dressed in a black sweater and blue jeans, she sat on the edge of a large easy chair, digging her bare feet into the thick white carpet. She smoked clove cigarettes, one after another, taking one or two puffs, then lining the butts neatly in an ashtray like stacks of PVC pipe.

Even in her music, Ono continued the conceptual art tenet of challenging. But the outrage that met her movies, like “Film No. 4,” a sequence of 310 bare asses, was a lot different from the vilification she endured as the “women who broke up the Beatles” and for her music, a wailing shriek, a multi-phonic scrawl, a primal scream.

In fact, primal scream is where much of that early music came from. While John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album was an articulation of his primal scream therapy with Arthur Janov, Yoko Ono’s Plastic Ono Band album was the scream itself. “Well we were both involved in it, John more heavily,” she said. “I was just going along with it, but it was a very important experience for us. It was so funny because somebody sent us the book called “Primal Scream” and John said, `Somebody’s doing you.’ Because I was screaming before that, right?”

In another light, say that of the 1970s avant-garde or early punk music, Ono may have been viewed as an Avatar of Angst. She certainly had part of the requisite background with a traumatic childhood. She was separated from her parents during the Tokyo bombings of World War II and left to forage in the countryside for food and shelter. She rarely spoke about those days, yet, it’s the kind of experience that for many artists would form the core of a career, but Yoko treats it dismissively.

“Well the only thing that really gave me a big impact is the sky,” she insisted. “This was very funny because even when I was starving, when I was evacuated during the war, the sky was always beautiful. And then I came back to Tokyo and the whole of Tokyo is bombed out, and I thought, wow, this can’t be Tokyo. But even in a bombed out city like that, the sky was always impeccably beautiful. And everywhere I go, I always remember how beautiful the sky was. And that’s in London, San Francisco, LA, anywhere. That was the thing that always kept me going, the fact that the sky never changed.”

I note that she’s kept the sky on the ceiling of her office and it never changes either. “No, it falls apart,” she laughed. “Sometimes you have to repaint it all.”

For listeners and critics alike, there was little context for Ono’s sound. It would be six or seven years before singers like Joan La Barbara, Meredith Monk and Diamanda Galas would emerge, and a few more years before their techniques would be assimilated into pop music by the B-52s’ Kate Pierson and Cyndi Lauper. The only singer who approached her sound in the sixties was avant-garde diva, Cathy Berberian and her performances on works by Luciano Berio.

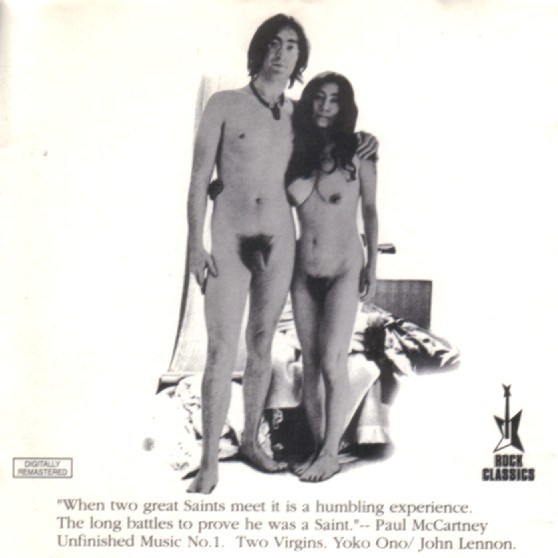

Ono’s own style seems to have emerged more from the dissonant, cross-referenced collages of Karlheinz Stockhausen, and the aleatoric cross-currents of Cage. Those influences, picked up during her two year stint at Sarah Lawrence College in the late 1950s, and reinforced during her 60s associations with many of these artists, could be heard in her early records with Lennon, Unfinished Music No.1: Two Virgins (Apple) and Unfinished Music #2: Life with the Lions (Apple). “We made a point that it’s an unfinished music and you can put something of yourself over a track,” she recalled.

But of course, Unfinished Music #1 was infamous for the full-frontal nude shot of John and Yoko. “I think people were just going crazy over the cover and didn’t even get the vinyl out of it,” she laughed. “But the idea is like the Karaoke idea. Our track is unfinished and you finish it. I thought that was something that might catch on but I don’t think people even considered it.”

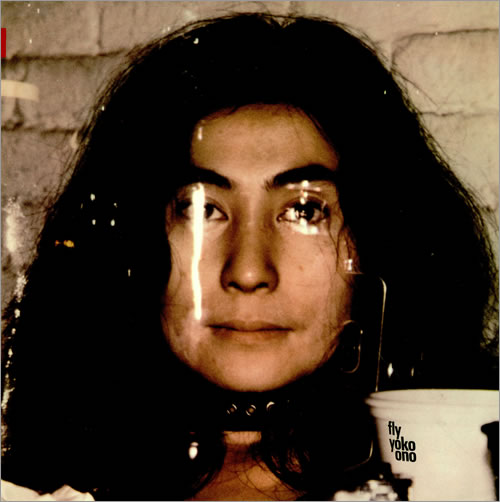

Like Cage’s chance music or even Brian Eno’s Discreet Music (Editions EG) processes, Ono liked to set things in motion and see what happens. On Fly (Apple) she used instruments from Joe Jones Tone Deaf Music, devices that were a cross between a Rube Goldberg contraption and a windharp. Set in motion, they’d go on their own path. “I liked that because it’s like my voice in the way that nothing else can affect it,” said Ono. “I’m just doing it and these instruments were just playing it. Nobody’s touching it. It’s like automatic music.”

Another influence could be found in Tibetan monks and the microtonal music of her native Japan. “I noticed a lot of kind of Japanese Kabuki kind of thing comes out of me too,” she said, punctuating it with a guttural shout. “I’m thinking, ohhh probably that’s something that I got from my childhood or something like that.”

But Ono is dismissive about these and other sources. Instead, she cites rock and roll. “I think it has to do with the rock beat, that my voice came out that way,” she claimed. “I was doing that sort of thing, voice modulation, using my voice as an instrument even before that in the avant-garde and then I did it with Ornette Coleman and jazz and all that. But it was quite different. The beat itself helped me to sort of produce this sort of famous Yoko Ono, [here Ono lets out a shriek], you know that one. And also I had to go over the top because they were playing electric guitars and they were very ruthless about it.”

They were ruthless because they were probably trying to keep up. I heard a DJ on WNTN in Newton Massachusetts who had the courage to play Yoko Ono’s Plastic Ono Band album in the early 70s. He remarked that “the sign of a great musician was whether the band behind them really kicked, and this band really kicks.” Some claim that Lennon did his best playing behind Yoko on pieces like “Why” and “Why Not” or the slide guitar on the trancey “Mind Train” from Fly. Watch the Live Peace in Toronto video and it’s evident that Yoko Ono is the only one on stage who is in clear command as Clapton looks bewilderingly at his guitar, trying to get some feedback and Lennon keeps rushing to Ono’s side, probably looking for direction.

Listening to a piece like “Why” as her voice flutters, and howls and splits into multi-phonics, you can hear the stunning control Yoko had over her voice. The state she obtained was more like a trance, where the body becomes a pathway for something beyond. “When I do an improvisation, I free myself totally and just allow sounds to come out of me,” she said. “So those are the sounds that came out of me.”

Yoko’s explorations may have caught the rock audience unawares, but she captured the ears of avant-garde players like Ornette Coleman. “I was doing a concert in Paris of my own work,” said Ono. “and after the concert was over, somebody said that Ornette was in the audience and introduced me to him. And he immediately said, `I like what you are doing.'”

Ono, who is self-deprecating about her own work didn’t take him seriously until he invited her to perform with him at the Royal Albert Hall in London. She subsequently recorded with Coleman’s trio on Yoko Ono and the Plastic Ono Band.

Yoko steadily moved away from the avant-garde, partly because of audience reactions. “It was a pity that I couldn’t have done more of that,” she said remorsefully. “And in a way I think the world shut me up. There’s a certain point when an artist gets totally discouraged. In the beginning I wasn’t listening to them, I was just going on with my thing. But there was a point when I realized that I couldn’t record another song like that and put it out, because nobody’s going to buy it.”

So Ono moved towards Rock and Roll with one of its greatest creators as a mentor. “I was sitting in Beatle sessions and started to listen to their music,” she recalls. “In the beginning I was thinking, `Oh I’m sitting here and I should be thinking about my songs or my music. Then I started to listen to it, and I thought, this is great. It’s people’s music.”

Yoko’s pop material has always been a mixed bag. Ono singing pop songs was a lot like Placido Domingo singing the Beatles, it’s the wrong instrument for the genre and yields up the campy Elvis imitations of “Midsummer New York”, the corny space ballad, “Spec of Dust,” and the abysmal confusion of Starpeace (Polydor), her album from 1985. The failure of Starpeace is all the more surprising given the production of Bill Laswell and playing by Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, percussionist Aiyb Dieng, violinist L. Shankar and drummer Tony Williams. Yet, there’s no denying the power in some of her most personnel songs like “Walking On Thin Ice”, “Kiss, Kiss, Kiss,” “No, No, No” or “I Felt Like Smashing My Face In A Clear Glass Window.”

Ono believes in letting it out, imperfections intact, especially on Seasons of Glass, her potent first album after the death of Lennon. She’s always been criticized for her cracking voice and suspect intonation, but on Seasons of Glass, those were the shudders of emotion. “There’s some people who believe that music is like a fashion show,” she observed. You show your best foot forward and you look thin and beautiful and no blemish on your face. Some people believe that it’s actually sort of showing your guts, bringing your guts out. I’m one of those people who believe that you should really expose your heart, expose your emotion. So in that sense sometimes my sound is not pretty.”

Since this interview, Ono has spent most of her time tending to the legacy of John Lennon and continuing her engagement in political causes, most recently protesting “fracking.” engaging in political causes. In 2009 she released Between My Head and the Sky, a rocking, punked out, sometimes free-form excursion that held echoes from the original Plastic Ono Band album, and was best when it played to Ono’s strengths as a non-lyrical avant-garde singer. That was followed in 2012 by Yokokimthurston, an even more avant-garde free form affair with Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth. She’s even performed with Lady Gaga. Check out the dueling shrieks at the end of this video.

Yoko Ono may be the most misunderstood artist of the 20th century, yet, here she is, still going in the 21st. Happy Birthday.

~John Diliberto ((( echoes )))

Portions of this article originally appeared in Jazziz Magazine in 1992 and on Echoes 1992

Thank you John, for showing us that there is always more than meets the eye (or ear).

john, please. may i call bs?

Yoko cut the crap already. You have already been told

countless times to cut your OBLIQUE STRATEGIES

by naming DIAMANDA GALAS AND MANY OTHERS

as influencees.

Please stop lying. You will remember foremost

as ONO THE GLUTTON.

sorry.

Given that Yoko Ono’s first recording predates Diamanda Galas’ first by a dozen years, and that the bulk of Ono’s work was recorded before 1982, when Diamanda Galas’ Litanies of Satan was released, I don’t think there can be any doubt in which direction the influence, if any, flows. But don’t let the facts get in the way of an apoplectic rant.